HALESWORTH

AN ECOLOGICAL SOCIETY

Denis Bellamy

&

Ruth Downing

2006

(2nd Edition)

“But social history does not merely provide the required link between

economic and political history. It has also its own positive value and peculiar

concern. Its scope may be defined as the daily life of the inhabitants of the

land in past ages: this includes the human as well as the economic relation of

different classes to one another, the character of family and household life,

the conditions of labour and of leisure, the attitude of man to nature, the

culture of each age as it arose out of these general conditions of life, and

took ever-changing forms in religion, literature and music, architecture,

learning and thought”.

C.M. Trevelyan (1944)

Summary and Aims.. 7

Preface.. 9

1 Introduction.. 13

1.1Cultural

ecology. 13

1.2 Giving. 15

1.3

Taking. 16

1.4

Towards a new history. 17

2 People of the Blyth.. 23

2.1

Topography. 23

2.1.1

Blything Hundred. 24

2.1.2

Communications. 25

2.2

Halesworth and the ‘nook’ communities. 29

2.2.1

Parish boundaries. 34

2.3

Social structure. 37

2.3.1 Lordship. 37

2.3.2 Neighbourliness. 39

2.3.3 Fraternity. 39

2.3.4 Kinship. 40

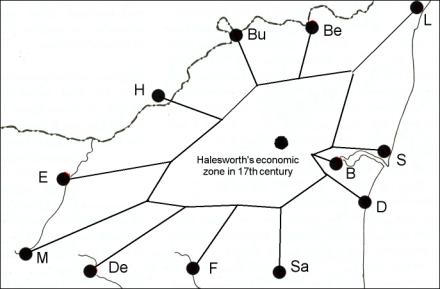

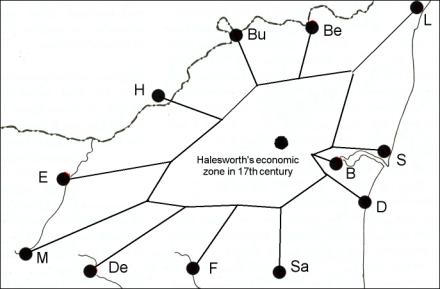

2.3.5 Economic networks. 40

2.3.6

Land ownership. 41

3 The ‘sea’ of rurality.. 43

3.1

Course of urbanisation. 43

3.2 The ‘Chediston Story’ 47

3.2.1 The people. 49

3.3 The romance of rurality. 52

3.4 Past

in the Present 54

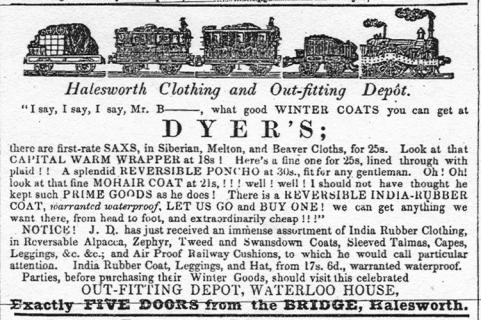

4 Manufacturers.. 57

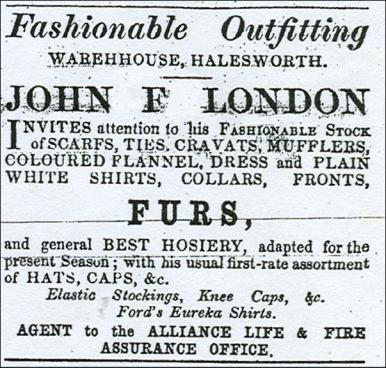

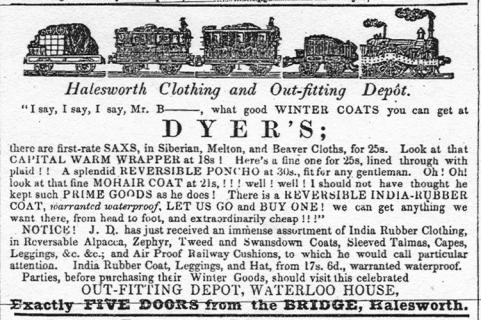

4.1 Needs and wants. 57

4.1.1

Food and drink. 57

4.1.2

Clothing. 58

4.1.3 Housing. 60

4.2

Trading networks. 62

4.2.1 The high-trust culture. 63

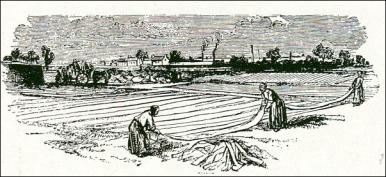

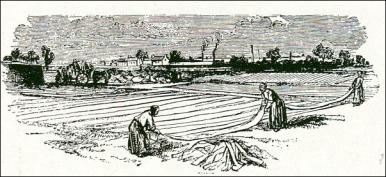

4.3 Money from hemp. 65

4.3.1

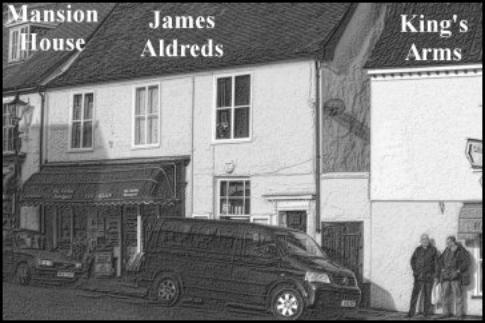

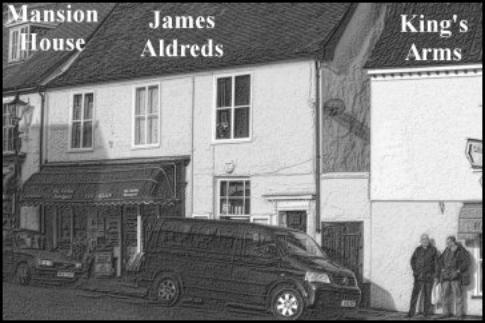

James Aldred; manufacturing draper 71

4.4

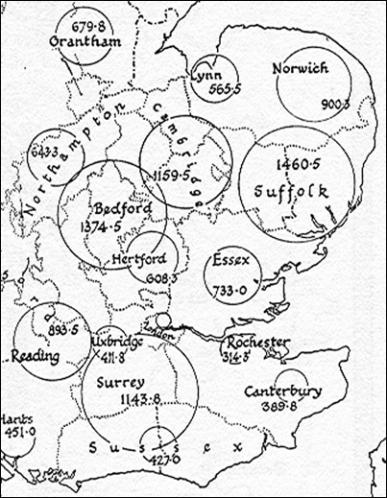

Money from malt 73

4.4.1

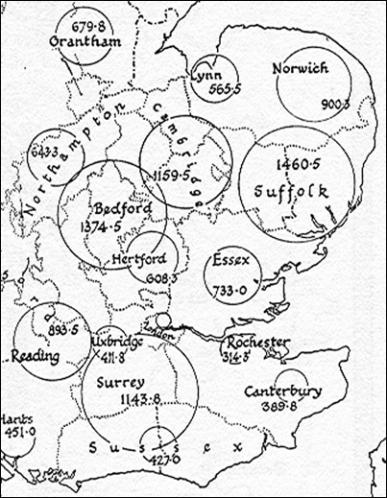

East Anglia and malting. 73

4.5 Botanical riches. 75

4.5.1 Badeleys and Woodcocks. 76

4.5.2 William Jackson Hooker 77

4.6

Barley business. 82

4.6.1 Malting at Halesworth. 88

4.6.2 The malting infrastructure. 90

4.6.3 Patrick Stead. 91

4.7 Trading on a restless coast 94

4.7.1 ‘Murder of Southwold’ 96

4.7.2

Malting; an historical milestone. 97

4.8

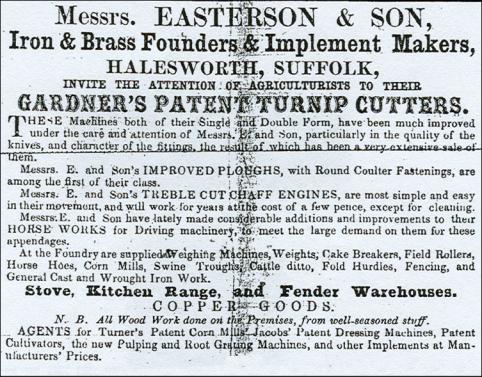

Other manufacturing businesses. 99

4.8.1

A truly local newspaper 103

4.8.2

Mass production. 105

4.8.3 An educational model 108

5 Retailers.. 113

5.1 The retail network. 113

5.2 A spatial economy. 116

5.3

The retail community. 117

5.4 Occupations and status. 122

5.5

A seller’s market 125

5.6 Community directories. 129

5.6.1 Historical trends. 130

5.6.2 Use of directories for research. 131

5.6.3

Halesworth in directories. 132

5.7 Ebb and flow of traders through directories. 134

5.7.1 Population dynamics of householders. 137

5.7.2

Retail establishments: 1838-2005. 140

5.7.3 No 1 The Thoroughfare. 143

5.8 A microcosm of consumerism.. 145

Chapter 6

Peopling the Townscape.. 149

6.1

Families. 149

6.1.1

Aldreds, Nurseys and Crisps. 149

6.2 The social pyramid. 152

6.3 1851- A turning point 159

6.4 Population. 160

6.5 Economic change. 161

6.6 People of the Census. 162

6.7 Education. 167

6.8 Charity. 172

6..9

Medical care. 176

6.10

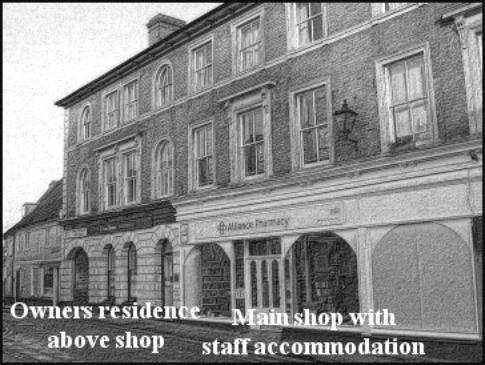

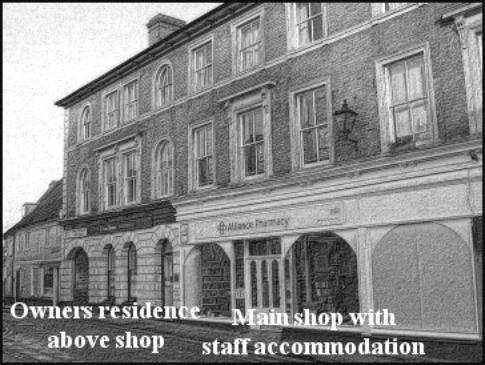

The Bon Marche comes to town. 178

6.10.1

Clothes with groceries. 178

6.10.2 The road to Roes. 182

6.10.3

Origins of the Lincolne family. 188

6.10.4 Department stores. 189

6.10.5 The Roe family. 191

6.11 The Sheriffe family: landed

proprietors and investors. 194

6.12

Butchers and bakers. 198

6.12.1 Samuel Kemp. 199

6.13

A spiritual background. 202

6.14 Independents in action. 204

6.14.1

The Pound Street Chapels. 205

6.14.2 A personal view of Roe & Co. 207

6.14.3 The Ellis family. 211

6.15

The force of individuality. 212

6.15.1 A resource to feed the imagination. 215

6.16 Chediston Street’s legacy. 215

7 A

Conservation Culture.. 223

7.1 A consuming society. 223

7.1.1

Consumerism and recreation. 225

7.1.2 Point of inflection. 227

7.1.3 Real growth. 229

7.1.4 Supermarket wars. 236

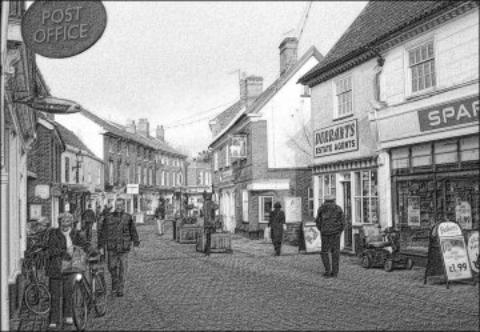

7.2 Symbols in the environment 238

7.2.1 In-coming. 238

7.2.2

Townscapes as interactive museums. 240

7.3

Partnership for sustainability. 242

7.3.1 Citizen stakeholders. 244

7.3.2

Planning by inclusion. 246

7.4

Post-industrial business. 248

7.5

A new culture partially revealed. 249

Postscript.. 255

Bibliography.. 259

Acknowlegements.. 261

This booklet is a local history of urbanisation as an introduction to

the topic of ‘cultural ecology’. Cultural

ecology is a subject for living in an overcrowded world. It is defined as the sum of all social

processes resulting from technological innovations, by which nature and people

are organised for production in a society based on ecological principles. In this context it is a tribute to local

cleverness and power by which a steady stream of Halesworth entrepreneurs

singled out a small market town in their quest for a better life. In hindsight

it was from this time we clearly all became part of nature in relation to our

devastating ecological impact upon the biology of land and sea. However, since the first humans began forest

clearance, all local human gatherings became ecological societies, but this

truth has only just broken through into human forward thinking in relation to

the impending catastrophe that faces the whole of humanity through

human-induced climate change. In this respect, ‘Halesworth; an ecological

society’ is a text of its time. The

aims are:

- to highlight the roles

of individuals and families who carried this upsurge in consumerism into

the 21st century, and connect their stream of social history

with the new age of sustainable development;

- to provide the basic

resource for an educational model of an interactive people’s history,

which illustrates how the worldwide web can provide a toolkit for people

to add their own input to an ongoing local narrative;

- to reinforce those who

are beginning to turn away from material goods as a source of happiness,

and are instead trying, with a minimum planetary impact, to maximise the

feeling they derive from every moment in contact with their cultural

heritage, whether this be a tree or a timber shop front in the street.

History used to be only about the

political arena of wars and the roles of famous leaders and thinkers. This national emphasis has changed, and

since about the middle of the last century, people described as social

historians have begun to look more closely at the experiences of "ordinary

people" and everyday life.

Recently, this view has been embedded in the concept of social history

being a continuation of a process of human evolution. Evolution is seen as a phenomenon of continuous change in which,

during the last two million years, we humans have imposed our will on the

environment as an outcome of our characteristic social nature. In this perspective we can see that for the

last two centuries we have been living in societies dominated by applied

ecology. According to this idea, the

history of every society, such as the increased prosperity of a concentration

of people in towns like Halesworth, has been a continuous process of resolving

the ecological problems of organising nature and people for production. These problems have been resolved by meeting

social needs that require the transformation of natural resources into goods and

services. ‘Ecology’ is thus defined as

a social concept where economic, ethnic, and gender conflicts, amongst others,

lie at the core of planet Earth’s serious, and some say terminal, environmental

problems. This is the reason why we

have undertaken to place the local history of Halesworth in this broad context

of ecological societies.

The concept of ‘ecological societies’

has great potential value and benefit for anyone interested in people of the

past who inhabited the houses and walked the streets of their hometown. This approach to local history was given a

boost by the coming of the new millennium, when it was realised there was a

link between the now distant past and the immediate future. A common feeling

was that a community with a solid history has a stable platform upon which to

become involved with future socio-economic developments, particularly in

relation to conservation of the built environment. Every building is part of a rich and complicated tapestry of

life. However, such is the speed of

change, that in a fraction of a lifetime, old buildings, open spaces and

curious nooks and crannies can be replaced with cash-generating placeless

development. A good grounding in social

history contributes to a community’s adversarial strength in putting a case for

conservation.

When this "new" social history

began to emerge in the 1960s, it was at first very much analytical; scholars

began to ask specific questions. How

much social mobility was there and why? What were the experiences of racial minorities,

immigrants, and women in British society? How did workers respond to the

industrial setting? How did migrants respond to the new industrial cities? But social historians also looked at the

institutions used by ordinary folk; in the City People study of

nineteenth century New York, the roles of the department store, metropolitan

daily newspaper, vaudeville house, and baseball park, were considered critical

to the emergence of a common urban culture by the many diverse people who

inhabited the city.

This was history written "from the

bottom up" becoming respectable.

Instead of the traditional academic approach from "top-down,"

social history has increasingly broadened to characterise the large mass of

those who appear only dimly on the pages of standard histories. At the same

time, social history has now fragmented into a number of discrete sub fields

including ‘family’, ‘women and gender’, ‘cities and suburbs’, ‘immigration’,

‘racial minorities’, ‘childhood’, ‘ageing’, ‘agricultural life’, and ‘workers’.

Since social history focuses on

experiences that touch the lives of everyone or their ancestors, it is of

immediate interest to most people. It provides them with a sense of where they

came from and how they came to be where they are. There is a knowledge gap to

be filled for the creation of a sense of continuity with the past in a rapidly

changing world. This is especially true

for children, raised in an age of atomic and neutron bombs, ‘global villages’,

television, VCRs, videogames, PCs, instant food, and moon travel. There is a gap in understanding the lives of

their parents and grandparents, whose childhoods included none of these

contributions to modern civilization.

In an age where ‘sustainable development

is a global catchword to the future, and ‘conservation’ is a widespread

behaviour to preserve heritage assets, social history provides the context and

explanation necessary to move into the future. It encourages the inclusion of

all peoples of a community, not just elites or founders. While the latter are

important, their roles are often exaggerated.

A broader coverage of all groups and organizations permits a more

accurate and complete record; it also encourages a wider participation in the

process of feedback and updating. This process of inclusivity is greatly aided

by the spread of computer literacy and links between families through the

Internet. Social history then, is a key

to the greater democratization of local history and local historical

organizations; broader participation also means more resources including

members, volunteers, contributions, new ideas and viewpoints. Democratic participation in compiling and

extending local history into the immediate present offers the participants

attractive possibilities of nostalgia, and at the same time the opportunity to

explain how and why their lives have changed, and how in many respects they

have remained constant. Many social historians are first and foremost people

talking about their own patch. Their work is deeply rooted in a local context

and their studies depend heavily on, and contribute to, knowledge of place.

Perhaps the most exciting approach used

by social and local historians is oral history, an effort that is now largely

restricted to the twentieth century. Oral history is valuable in a number of

ways. It fills in gaps that other sources cannot; it personalizes history; and

it involves people (both interviewee and interviewer) who can broaden the base

of a local historical organization.

We began to gather information about

Halesworth’s past in the context of social history as a resource for

communities planning their future. The

town really chose us for this project in that we both have long ancestral links

with Blything and Halesworth itself. We

have drawn on the work of other local researchers, notably Nesta Evans, Michael

Fordham, Michael and Sheila Gooch, and Ivan Sparkes, and have incorporated some

reminiscences and new materials of local people, such as the Newby family. Our novel contribution is to use our combined

experiences as an academic and a local genealogist who have collaborated for

many years on international projects in environmental education. This has

enabled us to place Halesworth in the context of social ecology, to show how

people of the past, and their links through kinship and neighbourliness, have

contributed to changing urban society with new cultural expressions. This story is in no way definitive, but we

hope it offers a picture of a developing community in broad brush strokes in

which the accomplishments and trials and tribulations of individuals and

families is entwined with a broader national stream of world development. It is

offered as a basis for others to add to and refine. The scope is defined in the town’s brochure produced to celebrate

the Festival of Britain in 1951:

Many personalities during the

centuries have played their parts in the life of this small community. They

have flitted across its life like actors in a stage play, and books could be

written concerning their work. Humour, pathos, and honest endeavour have

mingled and the story is unending. Their names are legion and the results of

their efforts with us to day. We can give to all credit for their work and say

with the poet:

"

Something attempted, something done,

To earn the night's repose,"

Finally, the project is a celebration of

Suffolk’s contribution to the ‘age of plenty’.

This began at a time when William Etheridge of Fressingfield emerged in

1749 from the closed community of High Suffolk’s woodworkers to design the ‘Mathematical

Bridge’ across the Cam to the President’s Lodge of Queen’s College,

Cambridge. William had previously been foreman to James King, master carpenter

during the building of London’s first Westminster Bridge. He then went on as a master carpenter to

design a road bridge over the Thames at Walton and the new harbour

installations at Ramsgate. He was one

of the last engineers of the ‘age of wood’.

William is the fifth great uncle of Ruth Downing. A new industrial iron age was initiated in

Peasenhall in the 1820s when James Smyth, the village blacksmith, established a

factory for the mass production of the first commercially successful

horse-drawn seed drill. James was the

son of James Smyth the Elder of Sweffling and Hannah Kemp of Rendham. Hannah Kemp’s father is the fourth great

grandfather of Denis Bellamy.

DB & RD: 2006

“CHARLES BARDWELL (1779-1833): Bardwell was a linen &

woollen draper and silk mercer who occupied Thomas Bayfield’s premises (Market

Place) between 1823 and 1833. In 1829

the value of Bardwell’s property was assessed at £14, meaning that he was

supposed to take one apprentice from Bulcamp (workhouse). In 1831-33 Bardwell contributed a £1 each

year towards the cost of ‘Watching and Lighting the Town of Halesworth’.

…….Owing to illness in May 1833 he asked Mr Fyson of Yarmouth to purchase for

him in London a variety of fashionable silks, printed muslins and dresses etc.”

“ELIZABETH

SCRAGGS: Elizabeth Scraggs was a dyer living and working in Chediston St

between 1827 and 1844. In 1817 she

married James Scraggs of Halesworth……..In the Returns of Paupers James is

listed as having a wife and four children to support. Between 1836 and 1838 their house in Chapell Yard Chediston St

was valued at only £1”

The

Hemp Industry in the Halesworth Area 1790-1850; M

Fordham (2004)

The main components of history are not things but

people. This was the ‘discovery’ of

George Ewart Evans, who pioneered the study of the British oral tradition and

thereby revealed and archived the sociality of Suffolk’s rural life. In so doing he democratised the study of

history, and projected it into an ecological dimension by revealing ordinary

people’s living relationships with natural resources. Cultural ecology was actually first presented as a mental picture

by C.M. Trevelyan, ‘father’ of British social history. Since then, the term ‘cultural ecology’ has

expanded from the realm of the historian to cover the topic-web necessary to

link social activities with the origins of the natural resources that make them

possible. Culture is used in the sense

of a set of ideas, beliefs and knowledge, which unite society in a shared

course of action.

George Ewart Evans also worked at a time when there

was a revalidation of the historical artefacts of agriculture, such as

implements and buildings. There came a

shift in emphasis within museology from viewing them as the cultural heritage

of crafts-people who made them. Before,

they were seen as inert scientific specimens, now they are enormously charged

objects that stand as symbols of power relationships. Key concepts of social history are ‘kinship’, that is to say, how

different cultures interpret biological relationships, and ‘reciprocity’, the

idea that societies are bound together by the exchange of gifts, meaning

favours and services as well as material objects and money. Giving and taking are now central concepts

of economic development as the international community moves uncertainly

towards global legislation for a sustainable future. In this context there is an increasing historical emphasis on the

‘policy community’. Public policy is now the crucial way in which society is

kept together and connected. Members

of the conservation movement can be envisaged as a policy community that

emerged after the adoption of the World Conservation Strategy in the

1980s. Historians can now study a whole

raft of policy documents on sustainable development and conservation of resources,

and then look at how local officials interpret them and local recipients, as

stakeholders, respond to their transcriptions.

George Ewart Evans was situated deep in Suffolk

during the 1950s when mechanisation was taking over every aspect of rural life,

and shattering the racial and cultural unit that had defined English people

since the time of Chaucer. However, in

the face of change, his message was the paradox of sociality, namely that the

mass of people keeps a continuity, which is ever changing; yet forever

remaining the same. An important aspect

of this dynamic social continuity is the recurring hopes and aspirations of

individuals, which depend directly or indirectly, on local natural

resources. These environmental

connections provide the drive for family betterment that maintains statistical

inequalities in family fortunes. From

generation through generation, mechanisms that convert natural resources to

wealth also bring about inequalities in its systems of distribution. The existence of this socio-economic

phenomenon during the first half of the 19th century is evident in

the above quotations describing the relative wealth of two Halesworth families,

the Bardwells and Scraggs. A hundred

years later the Bardwells and Scraggs were long gone, but the prosperity gap

between Chediston Street and Market Place remained and had actually

increased. In fact it is a theme of

Michael Fordham’s work that the ups and downs of poverty have always provided

an undulating baseline to Halesworth’s rise to modern prosperity, and it was in

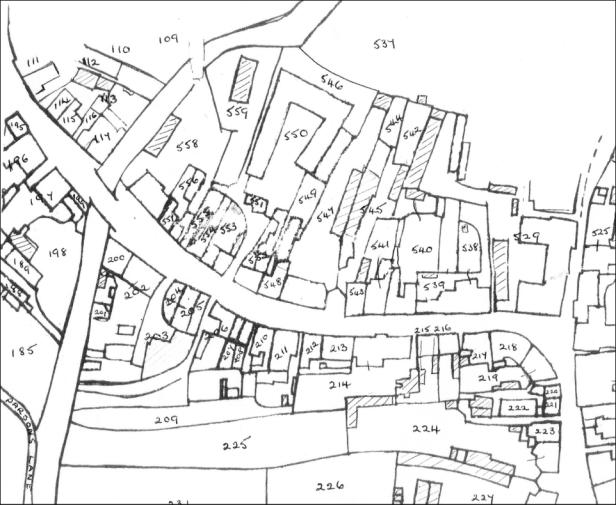

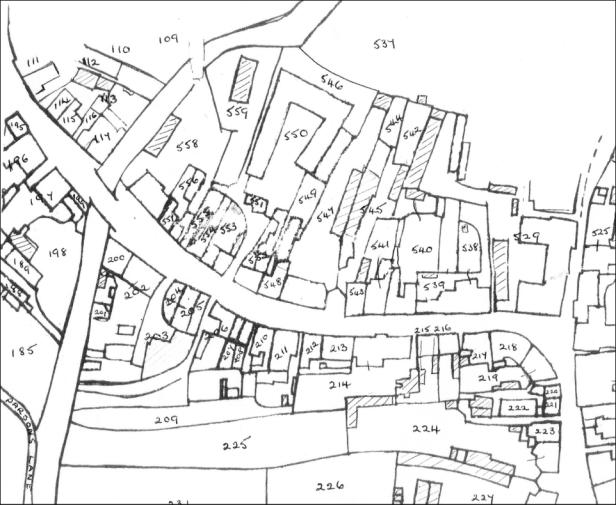

Chediston Street that its depths seemed always to be plumbed (Fig 1.1).

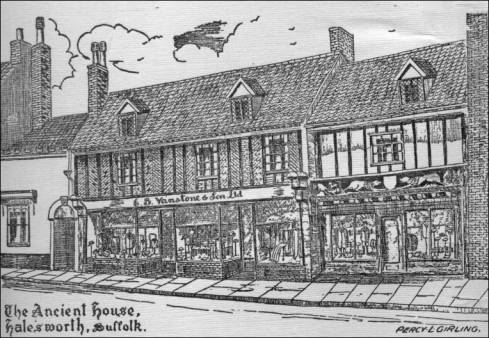

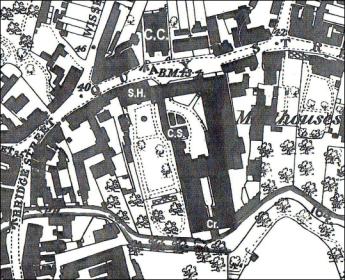

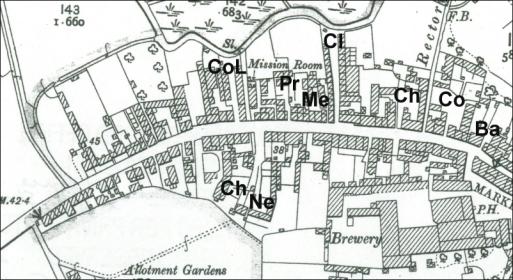

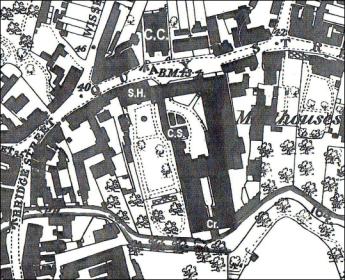

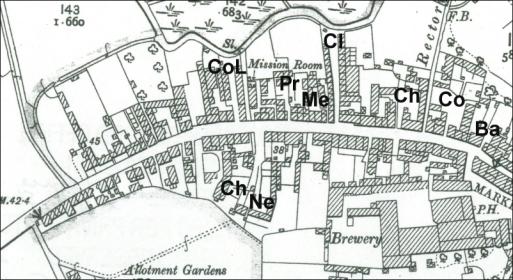

Fig 1.1 Past times in Chediston Street.

The relative situation of Charles Bardwell and

Elizabeth Scraggs actually identifies a point in time and space where the

‘birth of plenty’ sprang alive in Halesworth.

This was an era when people of small market towns throughout the land

were responding to a rapidly growing national economy. The birth of plenty actually opened up an

era where the two main pillars of cultural ecology were revealed as ‘giving’

and ‘taking’. These actions are really

two sides of the coin of world development, represented by the need to balance

the conservation of natural resources with their rate of exploitation.

‘Giving’ has a long history, which extends deep into

the Christian concept of ‘charity’ as an expression of care for all living

things, human love, and the giving of knowledge and resources. This revolutionary idea, which was

rediscovered by Wordsworth and Tolstoy, had been brought to the centre of

Christianity by Francis of Assisi six centuries earlier. It is as a concept that is most liberal and

sympathetic in the modern mood of sustainability; the love of nature; the love

of animals; non-violence, the sense of social compassion and, above all, the

spiritual dangers of prosperity and property.

The Franciscan idea of giving permeated the communities of Blything, for

we find that local people throughout the medieval period made bequests to the

Franciscan friars who had their local base in Dunwich. It has been taken up by

the post-modern conservation movement and expressed as ‘giving space to

nature’.

‘Taking’ is also deeply rooted in human nature,

where it is expressed through the satisfaction of the needs and wants of people

for natural resources to survive and better themselves. These days, the taking

of natural resources is represented by the forces of rampant consumerism, which

have complex sources of origins in the Dark Ages, when the ultimate prize of

life was the possession of worldly goods.

The Bardwells and the Scraggs of early 19th

century Halesworth lived barely a hundred yards apart, yet there was a great

economic chasm separating the shopkeepers and property owners who resided in

the Market Place from the artisans of Chediston Street, where two thirds of the

properties were valued at under £2 per annum. Bardwell’s transient existence in

Bayfield’s premises is also typical of the short life of many Halesworth

businesses that seldom survived across one generation. In this respect, there was a coming and

going and a rising and falling of families in their roles as shopkeepers,

craftsfolk and artisans, most of whom first appeared in the town as colonists,

seizing upon new opportunities for the exploitation of Halesworth’s potential

as a manufacturing and retail centre.

Very few families became natives.

For example in the space of a few years the property rented by Charles

Bardwell in the Market Place had passed through three families, Durban,

Woodcock and Baas. In this sense,

Halesworth was, as it remains today, a dynamic microcosm of retail culture, and

a model for evaluating factors that have contributed to its shifting sociality

and continuity. This dynamism has, for

two centuries, been expressed by the turnover and spread of families engaged in

the commerce of mass production linked with consumerism, a process that now

threatens the survival of all family retailers.

Any society has to make some provision for the very young and the very

old, for the sick and the disabled. In primitive societies it falls largely to

the family to make such provision, and in medieval Britain the Church shared

with the family and the craft guilds the responsibility for doing so. From the

16th century, the increased importance of economic causes of

distress and the declining authority of the Church resulted in the transference

of this burden to the community as a whole. The factory system, which destroyed

the home as an economic unit and the parish as an instrument of government,

ushered in an era of cyclical unemployment and urbanization, with concomitant

new problems of sanitation and new dangers to community health. Thus the social

forces, which encouraged the glorification of self-help, also promoted a

notable extension of state legislation concerned with social security.

The origin of such

legislation lies with the dissolution of the monasteries in the reign of Henry

VIII. Until then the almshouses and

hospitals of the Church had dispensed charity to those who did not benefit from

what protection the craft guilds could guarantee to their sick and aged

members, or to their families left destitute by the death of the breadwinner.

Bread giving was in fact a major charitable tradition in Halesworth. The Reformation itself coincided with a

variety of circumstances that increased the numbers incapable of supporting

themselves by their own efforts. In a loosely knit society with primitive

communications, re-employment could not keep in step with unemployment during

the economic upheaval accompanying the expansion of foreign trade, the

beginnings of capitalist farming and an influx of precious metals from the New

World. The lists of town paupers highlight the scale and how it was clustered

in areas like Chediston St and Pound St.

Relief,

however, was directed not at the population at large, but at the poor and

disabled. The method employed was to

place responsibility on the parishes, which were helped by a poor rate levied

on its working inhabitants. The

building of the great poorhouse at Bulcamp was the dread, not only of

Halesworth’s poor, but also clouded the lives of those of villagers for miles

around.

In the Halesworth of the 1851

census, the needs for charity were focused on unskilled and casual workers

struggling with low wages, the fear of accidents and diseases, and the dread of

slipping into that 'sunken sixth' of the workforce so close to the criminal

underworld, which Dickens wrote about. However, even in that

period, there was a resurgence of private charity and a resentment of state paternalism. To many merchants, particularly those who

had risen from little or nothing, paternalism was an anathema. Paternalism produced the poor laws, but

this generalised form of relief was no more acceptable to the town merchants

than indiscriminate monastic almsgiving had been. They set an example by

contributing more than half of the vast sums of money provided for private

charities, which were, in the long run, probably more effective than state aid

for the poor. Nevertheless, an increase of vagrants, beggars and petty criminals

forced itself on the attention of the authorities, which responded with hard

labour in Ipswich prison.

The original administrative unit for Halesworth was the ancient

pre-Norman unit of the Blything Hundred.

The

assimilation of Poor Law and Sanitation within a single framework, followed by

the transformation of the Local Government Board into the Ministry of Health,

defines the emergence of an essentially modern outlook on the functions of

government. This is an outlook that

transcends the traditional conflicting claims of social justice and social

privilege. It focuses on the satisfaction of basic human needs as the yardstick

of good government. An expanding

knowledge of the nature of human needs, also discloses vistas of unrealised

possibilities for rational co-operation between human beings. The latest expression of human needs is

‘sustainable development’, with its requirement for local and global

cooperation to protect the goods of environment for future generations.

A modern overview of ‘giving’

demonstrates that the medieval concept of charity is equated with what is now

organised as the machinery of social security.

However, people in the modern world are still embedded in a complex

system of giving, which involves government agencies, insurance companies and

charitable trusts. We are surrounded by

a network of cultural organisations set up to provide safeguards not only

against poverty, sickness or accident, but also to protect local and global

green/built heritage assets. Halesworth’s charity shops indicate how the desire

to give can permeate a community.

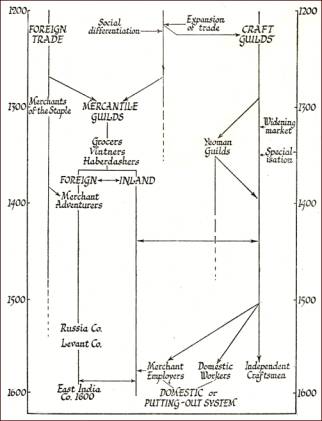

Commerce, that is the buying and selling of things,

is one of the oldest human social activities.

Historically it covers a vast range of scale, from the open stalls in

Halesworth’s medieval market place, selling homegrown produce and hand-made

wares, to the shelves of the Rainbow supermarket brimming with choice,

occupying several acres. Yet the same

human qualities appear at all these levels; the choices to be made between two

or more people vending the same objects, the different techniques of buyer and

seller, the urge to make a keen profit, or snap up a bargain, and the bustle of

the market place as a social milieu. The Bardwells and Scraggs also highlight

the other activity of towns, namely making things. Both families were connected with the linen trade, Bardwell as

seller and the Scraggs as dyers of locally made hempen cloth. The two groups, retailers and manufacturers,

have been an integral part of Halesworth’s economy down to the present

day. It is convenient to class them

together as ‘traders’, who mediate between the taking of natural resources and

the selling of goods made from them to meet the needs and wants of their family

customers.

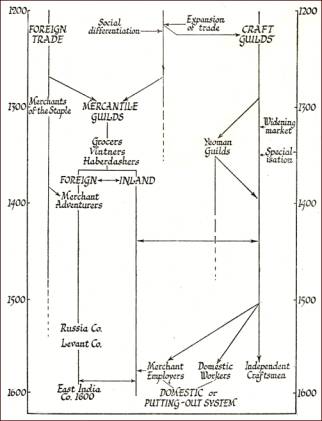

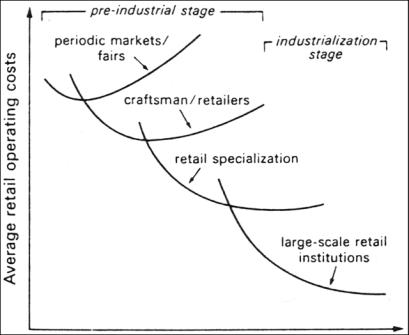

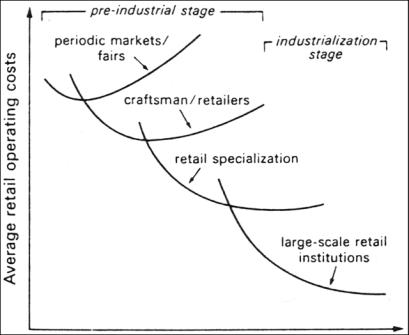

In a national context, specialised traders had first

emerged as townsfolk in the 13th century. Their aim was to satisfy an increasing and never ending demand

for goods and service by people in the town’s immediate surroundings and within

the town itself. These were needs that

could not be met by the traditional intermittent retail outlets of fairs,

markets and itinerant hawkers. In the

last quarter of the 18th century, there was a massive expansion in

the number of small shopkeepers listed in Halesworth’s trade directories, which

from the early 1820s was associated with a widespread shift from the

self-sufficiency of rural families towards a dependence on what has been called

the ‘shopocracy’. This phenomenon,

described as the ‘birth of plenty’, was driven by an ‘economic engine’ powered

by the coming together during the 18th century of four basic

factors;

- secure property rights;

- science applied to the mass manufacture of reliable goods;

- local availability of bank capital;

- improved transport and communication.

These were the necessary conditions for the 19th

century revolutions in manufacturing and retailing, which forced Halesworth

from a Suffolk backwater into the mainstream of East Anglian trade with the

Metropolis.

Specialisation of labour was the transmission drive

that increased the prosperity of artisans, and channelled power from

manufacturers to the dynamics of the retail trade. The retail machine was fuelled by the rising purchasing power of

families who were able to partake of the increased availability of cheap,

mass-produced goods. Bankers emerged as

individuals and partnerships from amongst those who had made good in trade, and

lawyers appeared to address the legal matters associated with increased numbers

of property owners, manufacturers and traders.

Halesworth was a Mecca for these two new categories of middle class

specialists, who established themselves in brick-built mansions midst the

timber-framed houses.

Evidence for the growing

social diversity of market towns, and their underlying family dynamics, comes

not only from the numerous trade directories that were published at this time,

but is also quantified in census records, wills, newspapers and parish books.

This information also illustrates the following important features of business

development:

- family businesses were relatively short-lived;

- economic development was largely in the hands of people who were

not natives;

- dowries played an important part in financing and stabilising

family businesses;

- partnerships were a way of gathering a critical mass of capital

and spreading the investment risk;

- success was associated with innovations in production and

marketing;

- know-how was exported by emigration of individuals, who, in their

turn, joined an expanding global quest for prosperity.

In relation to the above

issues connected to the changing human condition within nature, ‘Halesworth’

takes a view that the prosperity of the town ebbed and flowed when it did

because of its topographic history and who decided to live there. This views history as an unbroken tradition

carried forward by a succession of people building on the contributions of

previous generations. On the other

hand, there was also a coming together of people in the late medieval period,

which generated a new sense of community, based on a novel understanding of the

needs they shared and increased knowledge of the available means for satisfying

them. This perspective views history as

a process of ecological transformation.

Both propositions highlight

the need to define a subject that integrates the march of humanity with

occasional changes in environmental awareness, to explain how culture has come

to its present state from within a local ecological infrastructure. Halesworth, and hundreds of towns like it,

are ‘images’ of commercial communities that help towards this

understanding. The helpful

characteristics are:

·

the communities are small enough to function as

historical models with many different levels of understanding;

·

and they exemplify many different types of disruptive

events, which differ in size, chronological breadth and capacity to produce

long-lasting effects.

In both respects, these small town models have a bearing on the

need to explain history as a blend of stable structures and discontinuities.

The main task of the ‘old

history’ is one of tracing a line of tradition to discover how continuities are

maintained between generations, and how a single historical pattern is formed

and preserved. The task of the new

history of cultural ecology is to define transformations that serve as new

foundations or the rebuilding of old ones in relation to the availability of

natural resources. The historical

continuities are the momentum of the retail trade and population growth. The discontinuities are changes in the

perception and use of natural resources (exploiting resources) and changing

attitudes to charity (conserving resources).

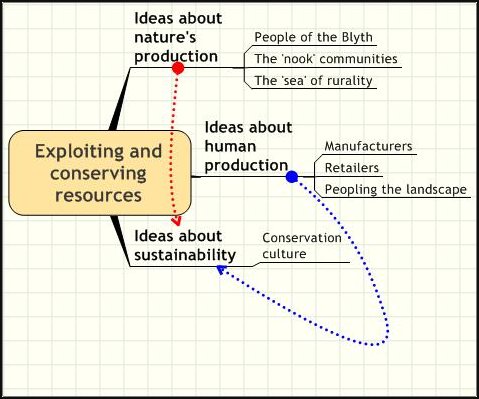

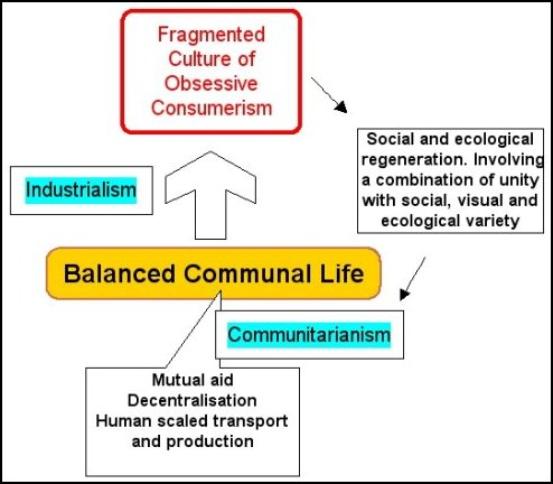

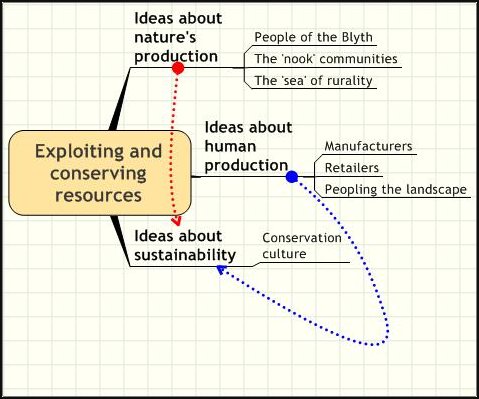

This holistic

knowledge framework is set out as a mind map in Fig 1.2.

In summary, ‘Halesworth’ deals

with historical causality within the town as a long-established retail

community, which in the mid 18th century became linked with national

discontinuities in the utilisation and scientific study of natural

resources. The account is built upon

two top-level concepts of

‘exploiting resources’ and ‘conserving resources’. Exploiting resources encapsulates ideas about human production,

and ‘conserving resources’ deals with ideas about nature’s production’ in relation

to people being a part of local and global ecosystems. Halesworth’s conservation culture began to

merge with, and influence, the long-established retail culture, which had been

based on the relentless exploitation of natural resources. At any one time culture is the outcome of the

interactions between the two activities, and at the present time cultural

ecology is having something of an upper hand in the way Halesworthians perceive

their town and its future. This

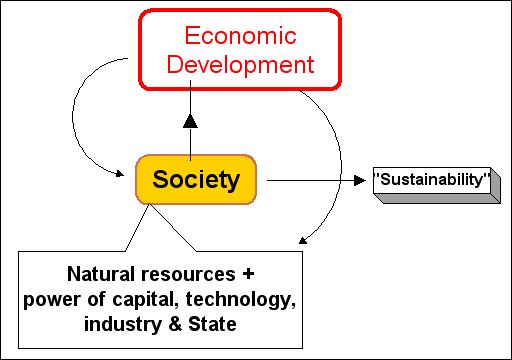

conceptual framework of ‘Halesworth’ is presented in Fig 1.3. The second level concepts in this mind map

define its chapters.

Figure 1.2 A map of

cultural ecology defined by its general concepts and levels

Figure 1.3

‘Halesworth’ topic map

1.5 Citizen historians

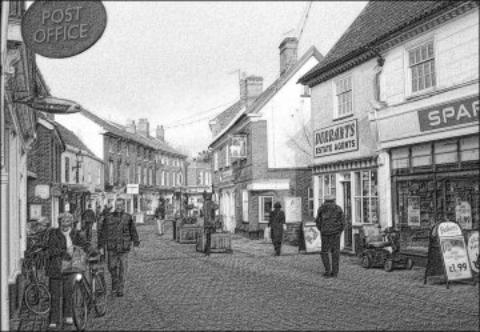

Questions about being a

community in both past and present are fundamentally about its physical basis,

and how people defined its boundaries. Answering them involves gathering

information about the local terrain as part of a wider social whole. People

interacting with terrain as a place to settle have added the human dimension to

create a 'landscape'. Their comings and goings to partake of its resources have

put down countless physical and biological markers of human development, and

also created a notional layer to the landscape. The notional layer is often

based on descriptions and opinions of people who have selected certain

physical, biological and cultural elements to conceptualise and communicate

'the spirit of the place' through literature and art.

'Halesworth’ is an exemplar to show people

how they can begin to visualise, and value their community's past, as part of

its present system of economic development. Indeed, community appraisal first

began with visual appraisal. It was Ralph Jeffrey, inspired by a book by De

Wolfe written in 1964 on Italian towns, who was one of the first to advocate a

formal system of environmental appraisal

De Wolfe advocated that this should start with

people making a 'visual enquiry' to establish the local 'spirit of the place'

by posing leading questions centred on

- its spaces;

- its decoration;

- its light

- and its buildings.

The Halesworth Conservation Area was first

designated in 1970 and amended and enlarged in 1979 and 1997. The latest development is the publication in

February, 2006 of Waveney District Council’s Character Appraisal and

Management Proposals/Strategy. This

describes the conservation area and its designated buildings, with some aims of

management and suggestions for amending the boundaries and listing more

buildings.

Actually, there are as many ways of evaluating a

community as there are people in it, the particular problems that bug them, and

the passions that excite them. However, a community appraisal based on its

landscape fits the requirements of producing a neighbourhood knowledge system

in its broadest context. It involves the presentation of an environmental

ethic, supported with knowledge of the historical, economic, and ecological

basis of community life. This is the foundation for environmental value

judgements required to launch projects to change things for the better. It

involves promoting an understanding of processes and skills by which this can

be done by participating citizens. Community appraisal should therefore equip

people to answer, and act upon, the following questions;

- what is good and bad about the neighbourhood, and why;

- what is missing from it, and what is superfluous;

- what could be done to improve it;

- is it harsh, soft, hostile, friendly, human-scaled, dramatic,

relevant to modern lifestyles;

- what are the factors for change and stability?

Seen in this context, the practical objective of ‘Halesworth’ is

to spur people to get involved with their community’s past in the present by

collecting information, writing stories about their lives, and generally

opening their eyes to the variety of cultural detail that surrounds them. The

aim is to set them thinking about their future society, and how it should be

expressed physically and economically in the rest of the millennium.

Regarding cultural change, the following

checklist of questions has been found useful:

- Delimitation of the sequence—when did it

start?

- The order of the sequence in relation to

time—what followed what?

- The order of the occurrence—why did it

happen in that sequence?

- The timing of the sequence—why did it occur when it did?

- Why did not something else occur?

- The rate of change—how long did the entire sequence take?

- Were certain elements of it faster or slower than others?

- Where there any differences between communities?

With the

addition of an occasional 'where?' to incorporate the spatial component, the

authors have found this checklist particularly useful when applied to the

various social dimensions of the history of Halesworth. From answers to these questions would come

the measurement of change, but full answers are not yet available for

historical analysts in many cases.

Nevertheless, the remembering of the questions in relation to the

availability of information has produced a provisional quantitative history of

the town. This traces its preindustrial

economy through the industrial phase, which peaked in the 19th

century to the present post-industrial society looking for ways to move into a

‘sustainable future’.

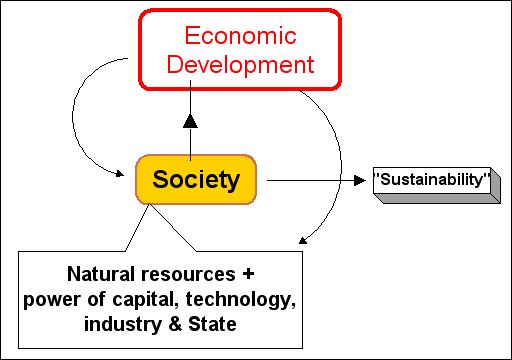

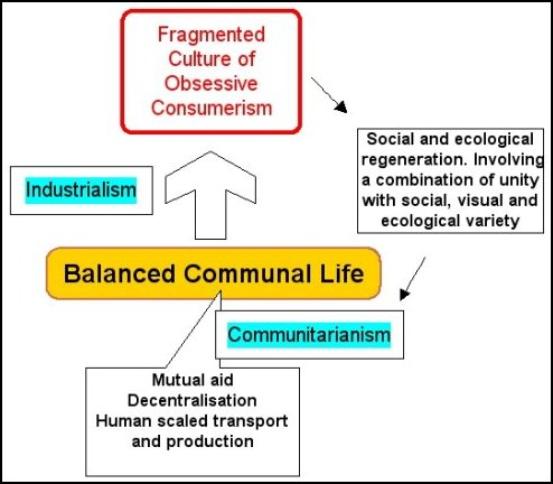

Sustainability

is not a scientific concept but a social idea. In this connection, it is not

really a unifying concept for planning, but is more a ‘generator of problems’,

which will only be solved by the community moving into a new cultural mode (Fig

1.4). To get there requires novel

community organisations by which the town’s stakeholders can control their

local authority representatives so that the collective will is carried

out. The great economic events of

industrialism happened mostly when the fate of communities was in the hands of

narrowly based local councils or cliques and ad hoc bodies like the Turnpike

Trusts and Navigation Commissioners.

Since the Reform Acts at the end of the 19th century there

has been a move towards regionalism, which is still in progress. A small outcome, that had a large local

impact, was the commandeering of Halesworth’s ancient market rights by the

District Council. A small, but

significant sign of the growth of communitarianism is that in response to local

demand they have recently been returned.

Fig

1.4 The Halesworth historical model of

social ecology

The stream ripples and glances over its brown bed, warmed

with sunbeams; by its bank the green flags wave and rustle, and all about the

meadows shine in pure gold of buttercups.

The hawthorn hedges are a mass of gleaming blossom, which scents the

breeze. There above rises the heath,

yellow mantled with gorse and beyond, if I walk for an hour or two, I shall

come out upon the sandy cliffs of Suffolk, and look over the northern sea.

George Gissing: ‘The

Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft’

In these three sentences George Gissing summarises the

essence of Halesworth’s setting as envisaged from the Town Bridge, where the

northern tributary of the River Blyth finally cuts its way free of Suffolk’s

great western Clay Plateau to seek the coast at Southwold. This relatively

small river runs due east from Halesworth to join the main channel of the Blyth

just outside the town, to continue through a broad expanse of drained marshy

pasture bordered by the low sandy hills of Blyford and Wenhaston. At Blythburgh the valley becomes a tidal

marsh with broad mudflats, and the river eventually enters the sea at Southwold

Quay.

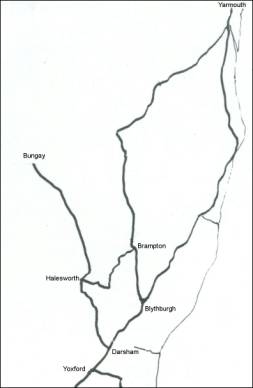

Fig. 2.1 Topographic diagram of Blything Hundred.

The development of Halesworth in modern times cannot be

understood without reference to the topography of this part of Suffolk,

particularly the river valleys, which cut the land into east-west

segments. In this connection, the town

is part of a larger pattern of human settlement that from the earliest of times

has been dominated by the complex drainage system of the River Blyth (Fig

2.1).

In fact, Halesworth’s topographic situation is reflected in its

ancient political position towards the centre of the Blything Hundred, about 10

miles from the coast. The Hundred is an ancient sub-division of the county

occupying precisely seven veins of the Blyth that have carved a broad arc into

the glacial plateau clays of High Suffolk. This clay plateau is at its highest

(about 55 metres) and flattest along a part of the western watershed, which

separates the parishes of Ubbeston (Blything Hundred) and Laxfield (Hoxne

Hundred). As inhabitants of the Hundred, Halesworth families have an

historical continuity with the Saxon people, or tribe, that had its capital at

Blythburgh. In this connection,

'Blything' is equated with 'people of the Blyth', a designation that may well

go further back in time to a coastal sub-division of land held by the Iron Age

Iceni. Blythburgh is the site of the Hundred's 'moot hall' and first came to

historical prominence as the religious centre of a branch of the important

Wuffinga kingship centred on Sutton Hoo.

This royal connection is evident from the Christian burial at Blythburgh

of King Ana in 654. It is recorded as

having a market in 1086 and in this respect its community had a functional

significance equal to the other Domesday economic centres of Suffolk, which

were at Kelsale, Dunwich, Ipswich, Stowmarket, Eye, Hoxne, Bungay, and Beccles.

Blything Hundred is a

well-defined territory, stretching from the Hundred River at Kessingland south

to another Hundred River, which separates Thorpeness from Aldeburgh. Although the old ways and skills of the

Blything may no longer be part of daily life, traditions of the earlier people

of the river valleys are still embedded within the ancient topographical

features of plateau, river and stream, which give the lands a powerful

sanctity.

In general, the Hundred boundary follows the contours that define the

Blyth watershed, but at some places it is marked by streams (becks), which are

also parish boundaries. The western valleys of the Blyth descend from the

fringe of the sparsely populated plateau settlements on the boundary, and are

characterised by having relatively steep, jagged, water-eroded sides, through

which minor roads follow narrow gullies. In relation to their size, relatively

small watercourses occupy these gullies, an indication that they were cut by

the flows of much larger volumes of water in the past. Some of these gullies

(locally named 'gulls') probably represent old melt-water channels of the last

glaciation. In this respect, the Blyth river system delineates a late glacial

landscape, with the land divided into several water-cut ridges running from west

to east. Although this coastal area was

no doubt attractive to the first post-glacial settlers, the corrugated ice-melt

terrain has always been a barrier to long distance north-south communication

through its settlements.

Towards the coast beyond Halesworth, streams cut through

sands and gravels (the Sandlings), which some believe were deposited from a

south-running ancestor of the River Rhine.

The outlets of all the rivers, from Kessingland to Aldeburgh, are

partially blocked by sand and shingle bars, and at the coast they are separated

from one another by soft cliffs undergoing rapid erosion. Safe havens are at a premium for coastal

trade. Occasional woods, copses, small

fields and tree lined hedgerows, considerably enhance the local character of an

intensively used landscape, which, in the 11th century, was the most

densely peopled region in England, with Suffolk having more than four hundred

of its churches and the main patterns of county settlement already set

out.

Historically, Halesworth seems not to have had an important

political position in the communities of the East Anglian coastal belt. It is just one of many irregular-shaped

parishes that are tightly packed within the Blyth watershed (Fig 2.2). Although there are archaeological signs of

occupation in the town going back to Palaeolithic times, there is no evidence

for Halesworth having been a major settlement in pre-Roman, Roman or Saxon

periods. However, the site of the

present church within an ovoid precinct could denote an early Christian

enclosure. A circular or curvilinear boundary is a feature of early Christian

church/chapel sites in Britain’s Celtic West.

Also, in this context, a short distance to the southwest is the

settlement of Walpole; the prefix ‘WAL’ coupled with ‘PWL’ (lake) may denote a

British (Welsh) settlement surviving in what became a predominantly Anglo-Saxon

area. The Norman overlords did not

fortify Halesworth, and their local administrative centre for this part of the

Shire was just outside the Blything Hundred, at Carlton.

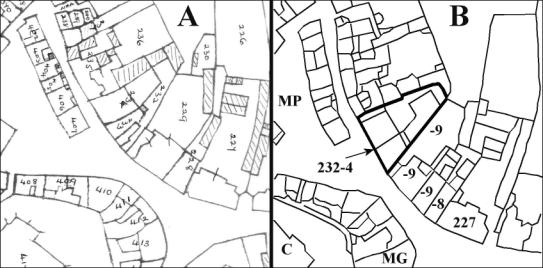

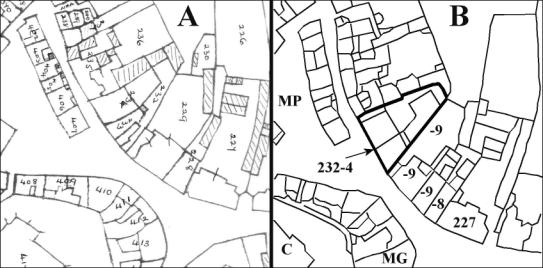

Fig 2.2 Parishes of Blything Hundred: pre 1855

From early

times, it appears that the settlement of Halesworth became important as a

stopover point in an old communication network extending from east to west across

the clay plateau to the coast. The

community lies on a branch off the main highway that follows the Waveney valley

from Bury to Yarmouth. This branch

turns off towards Halesworth at the market town of Harleston. As a minor route it crosses the Waveney to

traverse the great flat, open spaces of the glacial plateau at Metfield, where

it enters the Hundred, and then follows the northern-most tributary of the

Blyth down to Halesworth. After

crossing Town Bridge north of the church and market place, the road turns along

the northern sandy edge of the main valley of the Blyth through Blyford to

Southwold, a rare haven on the North Sea coastal shipping route between

Yarmouth and Ipswich. This particular

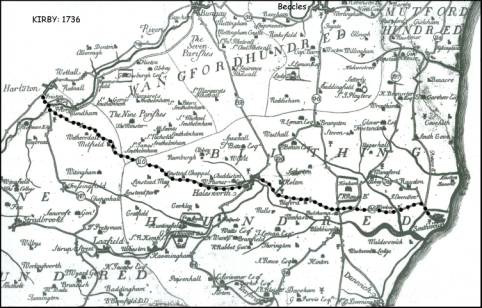

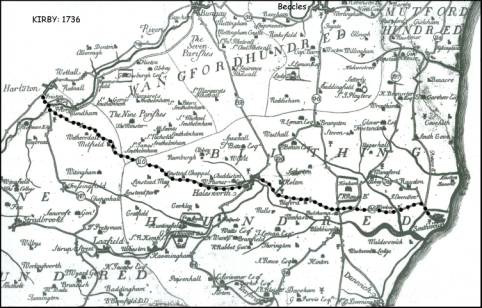

road from Harleston to Southwold, is evident on the earliest route map of the

area (dotted line; Fig 2.3). It has lateral branches at Halesworth, which go

north to Bungay, and south, via Walpole and Peasenhall, to Yoxford.

The remarkable

thing about Kirby’s road map, compared with modern maps is the large proportion

of villages that stand in isolation off the main roads. This is reflection of the poor quality of

communications and the self-sufficiency of the communities. A statute of 1555 made the parish responsible for

highways and this continued until about 1663. It was then that an Act of

Parliament decreed that ‘Turnpike Trusts’ should be set up. Until then,

surfaces were not too important because roads were only used by packhorses and

pedestrians during the summer. In 1706 Parliament created the first turnpike trust, a scheme by

which local business people could charge a toll for using a road, applying the

money received to maintain the road. After 1750 there was a ‘mania’ for

turnpikes. Just over eight hundred acts

were passed in the twenty years after 1751, and by 1830 there were some 1,100

trusts, created by around 4,000 separate acts, administering more than 56,000

miles of road. Whereas the first turnpikes had been in the counties close to

London, trusts after 1750 were set up mainly in the Midlands, and after 1790

were concentrated in the north of England, reflecting the changing pattern of

economic growth. Many of the trusts were fraudulently administered, and the

Turnpike Act of 1822 required trusts to keep accounts. Nevertheless, it has been

estimated that, by the 1830s, the turnpikes were investing about £1.5 million a

year in the United Kingdom road system.

Fig.

2.3 Kirby’s road map of 1736

The improved roads

allowed a significant increase of haulage traffic, passenger coaches, and a

national postal service. Local landowners, merchants, parish officials and

farmers were persuaded to become involved because it was to their benefit in an

expanding economy to have improved communications. Most of the western

Blything catchment is dominated by clay soils, which means that the Blyth river

system has always been prone to saturation and flashy river responses. Before hard road surfaces were introduced,

winter brought local upland travel to a virtual standstill. The Blyth valley marshes to the east of

Halesworth were a major impediment in all seasons. Before the marshes to the east of the town were drained for

grazing, the modern way south from the town to the main London highway was

through Walpole to Yoxford. In those

times, Bramfield was reached by a local ‘common lane’, from church to

church. This lane was then just a minor

parochial link between the two places.

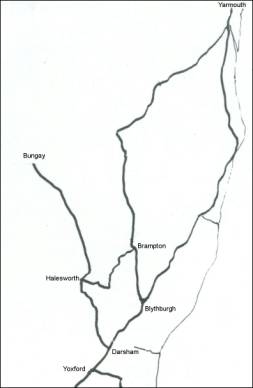

The situation only changed with the creation of the Bungay/ Halesworth/

Darsham turnpike, which, after passing through Halesworth, turned left at the

top of Pound St (London Rd.) to Bramfield.

From Bramfield it continued along a track called Beech Lane, which had

been improved by the trust for wheeled traffic to access the main coastal

turnpike from Yarmouth to Ipswich at Darsham. (Fig 2.4). It is thought that the flint-walled house at

the junction with the A12 was built for the toll keeper. There was probably another tollbooth in

Bramfield to catch traffic to Halesworth that converged laterally on the

crossroads in the centre of the village.

Fig. 2.4 Turnpike roads in North East

Suffolk

The economic stimulus given to trade by the

turnpike movement cannot be underestimated.

For example, Arthur Young the national advocate for improved

agriculture, with the interests of the countryside always at heart, rejoiced to

note that when a good turnpike road was made it opened out new markets. New ideas circulated through the

come-and-go of more frequent travel, and rents in the district soon rose with

the improvement of agriculture. On the other hand, he saw and deplored the

beginning of that 'rural exodus', which has been going on ever since, at a

pace, which matches the speed of improved communications. In his Farmer's

Letters (ed, 1771) he wrote:

To find fault with good roads would have the appearance of paradox and

absurdity; but it is nevertheless a fact that giving the power of expeditious

travelling depopulates the Kingdom. Young men and women in the country villages

fix their eyes on London as the last stage of their hope. They enter into

service in the country for little else but to raise money enough to go to

London, which was no such easy matter when a stage coach was four or five days

in creeping an hundred miles. The fare

and the expenses ran high. But now! A country fellow, one hundred miles

from London, jumps on a coach box in the morning, and for eight or ten

shillings gets to town by night, which makes a material difference; besides

rendering the going up and down so easy, the numbers who have seen London are

increased tenfold, and of course ten times the boasts are sounded in the ears

of country fools to induce them to quit their healthy clean fields for a region

of dirt, stink and noise.

However, without improving communications neither the industrial

nor the agricultural revolution could have taken place.

Fig.

2.5 Settlement of Halesworth in relation to the 50 ft contour of the upper

valley of the River Blyth, and its crossing points.

The picture of Halesworth as an

out-of-the-way focus for pedestrian and horse-borne travel was actually

reinforced by the granting of a market in the 13th century. This weekly market determined its local

inward-looking mercantile function for the next five centuries. The road connection with Southwold provided

its life-blood, which was trade with the coastal shipping route between

Newcastle and London. The peculiar

historical situation of Halesworth, off to one side of the main east-west

routes into East Anglia, also accounts for the fact that, today, in order to

reach the town from the main road network, the traveller either takes a winding

dog-leg route across the clay plateau from Harleston, or, if coming from the

south, has to make a sharp turn to the west off a relatively uninhabited

stretch of the A12 at Darsham.

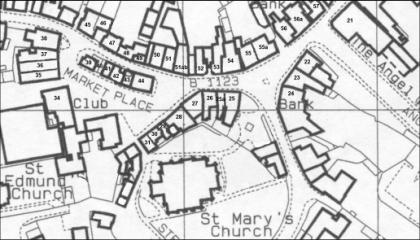

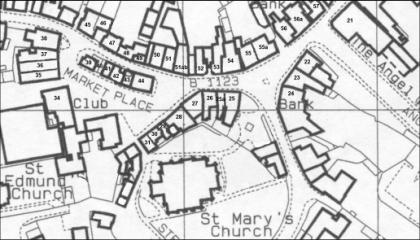

The position

of the settlement of Halesworth at the junction of the east-west and north

south communications through Blything has been critical to its history and

economic development. The key to

understanding the town’s strategic position is the 50 ft contour on which St

Mary’s church and the market place, as the first point of settlement, are

positioned. This is illustrated

diagrammatically in Fig 2.5. The 50ft

contour delineates the flood plain of the river at this point, and highlights

the fact that the largest flows of water descend from the clay plateau via the

southern valley. The roads along both

the north and south valleys immediately to the east and west of Halesworth more

or less follow the line of the 50 ft contour.

As stated above, the main north south route from Yoxford to Bungay

crossed the Southern Blyth at Walpole Bridge.

Bramfield (Mells) Bridge marks the site of an ancient crossing of the

river by the common lane that ran from Halesworth church to

Bramfield. As pointed out above, the modern

road to the bridge appears to have been a later development of a Turnpike Trust

to speed Halesworth traffic to the main London Turnpike at Darsham.

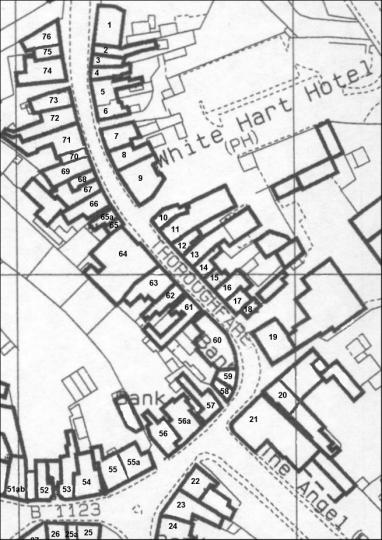

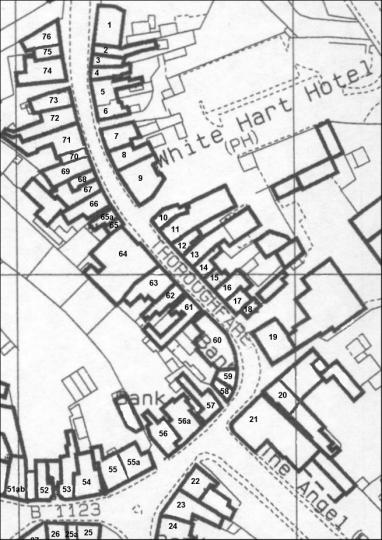

Routes from the northwest,

northeast, and north, focus on Halesworth’s Town Bridge below the church. This bridge marks the narrowest point of the

flood plain for crossing the Blyth, and the road from Harleston takes this

route from the church, down The Thoroughfare to the northern bank, where it

rises steeply again from the bridge up to the 50 ft contour. The approach to the bridge via the

Thoroughfare was constructed over marshy ground. In this respect, it was reported in the 1951 Festival of Britain

brochure for the town, that during excavations

in The Thoroughfare, when pipes for a sewer were being laid, huge quantities of

peat were brought to the surface. The town’s marshy heritage is still

evident in that the river is prone to flash flooding. The last major flood episode occurred on 12th October

1993, when the river overflowed its banks and extended from the bridge some 200

metres up the road to the south, flooding the car park, the park, and

properties on either side of The Thoroughfare. For most of its existence,

Halesworth was confined to the narrow strip of land between the church and

river and most of its medieval thatched buildings were packed tightly along The

Thoroughfare down to the Town Bridge.

It is here that most of its remaining timber-framed houses are found.

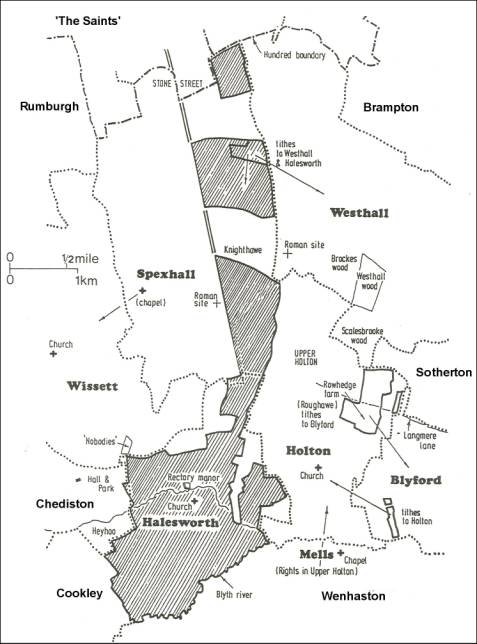

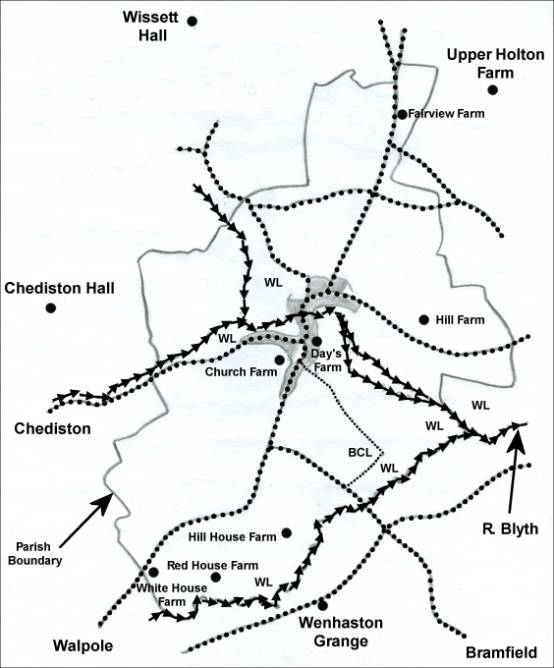

Halesworth is one of the smaller parishes of the Blything hundred

and is characterised for the most part by an angular boundary, which follows

hedges and ditches between fields. Only

its southern edge is marked by a natural feature, where the parish boundary is

delineated by the meanderings of the southern Blyth (Figs. 2.6-2.7).

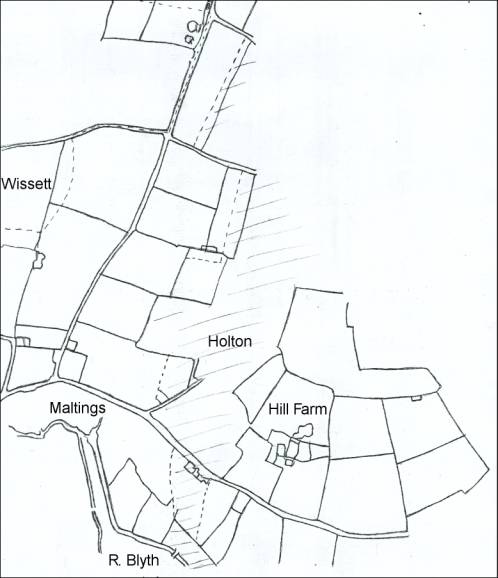

Fig 2.6 Parish

boundary of Halesworth (shaded) in the 19th century.

Parish boundaries are the

outcome of more than a thousand years of socio-economic history. They came after the primary process of

English settlement, which was followed by adjustments from time to time by the

exchange of land with neighbours. In

modern times, boundaries were changed radically in response to urbanisation and

the coming of the railways. For

example, Halesworth’s boundary was altered after the northern route of the

railway had cut off small irregular portions of the parish from its main

body. The last major alteration to

Halesworth’s boundaries was in 1934 and this more or less gave the parish its

present form (Fig 2.7).

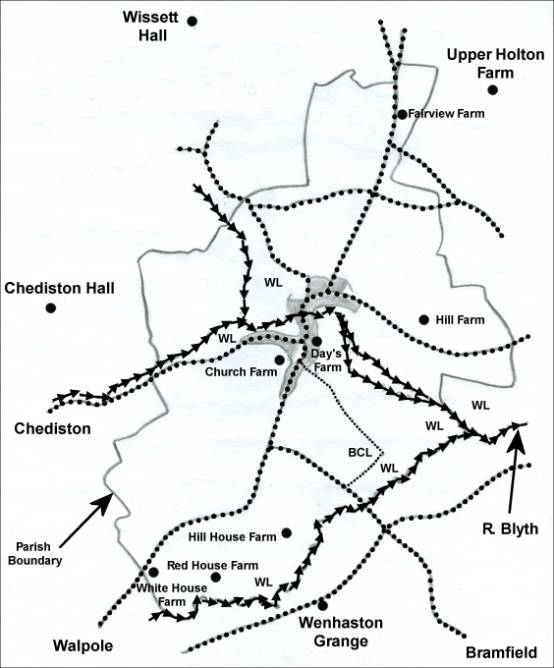

Fig

2.7 The position of Halesworth parish

(modern boundary) in relation to river, roads and farms.

WL = wetland; BCL= Bramfield common lane

Counteracting the forces of change was the need for geographical

cohesion on the part of the community.

A sense of place was maintained year on year by the ceremony of beating

the bounds. This was the annual

perambulation, led by the churchwardens, of young and old along an established

route that circumnavigated the parish.

Beating the bounds originated before the days of maps, and involved a

procession from one prominent feature to another, i.e. an ancient tree, a

stream or a hilltop.

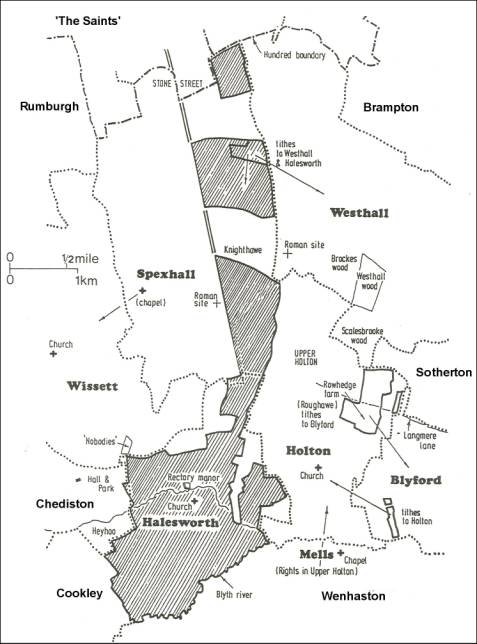

Fig

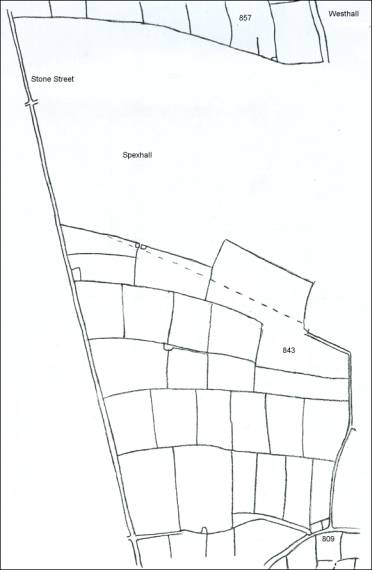

2.8 Compartmentation of outlying titheable lands (modified from Warner, 1987)

Shaded

area tithable to Halesworth

When the first map of

Halesworth was made in the mid 18th century, a detached portion of

Halesworth was embedded in the northern parish of Spexhall (Fig.

2.8-2.9-210). Subsequent adjustments of

this anomaly between Halesworth and Spexhall accounts for the narrow northern

extension of the parish parallel to Stone Street, the main road to Bungay. However, to understand the origins of the

parochial territory of Halesworth that subsequently conditioned its economic

development requires examining its condition and that of its northern

neighbours at the time of King

William’s Domesday Survey.

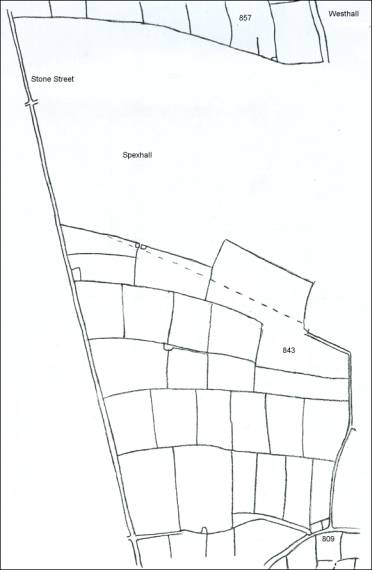

Fig

2.9 Halesworth in Spexhall (1842)

The fields of

Halesworth’s northern extension are rectangular and appear to have been planned

with their common axis running north to south (Fig 2.9), more or less following

the line of Stone St. which predates them.

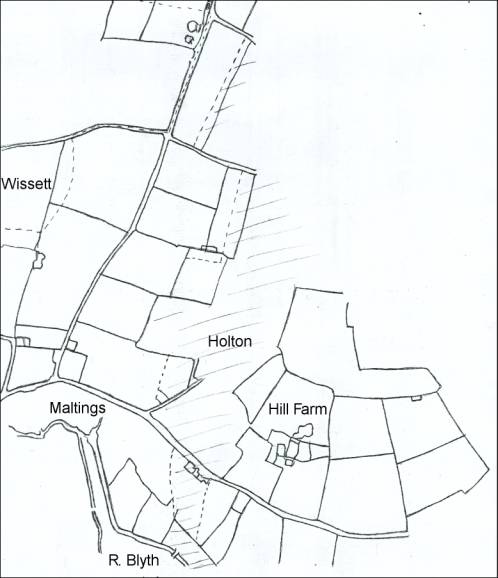

Nearer to the

centre of Halesworth, the boundary forms a projection, which contains the

homestead of Hill Farm (Fig. 2.10).

This ‘bulge’ is evidence of some kind of land deal in the past that took

place between Halesworth and Holton. It

could have been that Holton received a finger of land from Halesworth or that

Hill Farm was carved out of Holton.

There are no documented clues as what actually happened.

Generally, it

can be inferred from the way parish boundaries sometimes zigzag across the land

that negotiations over the enclosure of common land to make private fields,

and/or, the consolidation of estates on boundaries, which actually extended one

village and reduced another, was commonplace at the most distant points from

the centre of the village. All of this

might or might not be written down as a description of who owned which

fields. Mapping was a relatively late

process in community history and it not only fossilized community memory of

where one village ended and another began, but also signified ancient deals in

real estate, some of which have been traced back to Saxon charters.

Fig. 2.10 Parish boundary of Halesworth in relation to the Holton

and Wissett 1842

The Domesday Survey tells

that most of Halesworth was then in the hands of a powerful Norman baron, Earl

Hugh. He was pressing his claim on the

remainder of the village, which was contested by another of King William’s

henchmen, Earl Alan.

The following Domesday entry

for Halesworth is substantial and describes three estates with manorial status.

That is to say there were three lords with competing interests in land and

people.

Aelfric held Halesworth TRE as a manor with 2

carucates of land. Then 4 villans, now 5.

Then 7 borders, now 10. Then as

now 2 slaves. Then as now 2 ploughs in demesne. Then 3 ploughs belonging to the

men, now 2. Then woodland for 300 pigs,

now for 100. Then as now 4 acres of

meadow. 1 mill, 1 horse. Then as now 6 head of cattle. Now 10 pigs. 18 sheep. Then it was

worth 30 (s). now 40(s).

In the same vill Ulf the priest held 40 acres of

land as one manor. 2 borders. 1 plough

in demesne. Woodland for 6 pigs. 4

acres of meadow. 14 sheep. 2

goats. It is worth 5s.

To this manor have been joined 4 free men with 60

acres of land. 2 borders. 2 ploughs in demesne. It is worth 10s. And

Bigod de Loges holds these 3 estates from Earl Hugh.

It is one league long and another broad. It renders 7 ½ d in geld. Count Alan claims

the land of the aforsaid priest and those of 4 men through his predecessor and

his own seisin and the Hundred testifies (for him).

Earl Hugh also had interests in four parishes adjacent to

Halesworth, holding Bramfield as one manor, with properties in Walpole,

Thorington, Wenhaston and Wissett.

There is no Domesday entry for Spexhall and its eastern neighbour,

Westhall. Omissions of villages that

were later described as long-established communities are unusual, but not

unknown in Suffolk. This simply adds

to the air of mystery surrounding the origins of Halesworth, not least because

19th century Halesworth shared a fragmented northern boundary with

Wissett, Spexhall and Westhall.

It has been said that the landscape of Suffolk is still essentially

a Saxon one. The description of Domesday Halesworth as being one league long

and another broad, fits with the relative dimensions of the 19th

century parish. A clue to the

settlement’s connection with Spexhall could be Halesworth’s ownership of Domesday

woodland that could provide pannage for 300 pigs. This is a substantial amount of land that was probably sited on

unoccupied claylands to the north of the town.

Another large area of pannage was included in the survey of Wissett,

again amounting to 300 pigs. These figures are not accurate counts of actual

animals but were taken by the King’s surveyors to represent orders of magnitude

for comparative purposes. In the 1839

Tithe Apportionment, two blocks of fields belonging to Halesworth were embedded

in Spexhall, and there was also a part of Spexhall that was titheable in

Westhall. These arrangements indicate that this flat, and still relatively

uninhabited landscape, which is part of the watershed between the Blyth,

Wangford Brook and Waveney, was pre-Conquest wood pasture, with common land

rights held by villages to the south.

Subsequently, the block of land straddling Stone Street, a supposed

Roman road, became shared between the three communities, each having specified

amounts of common land, and these commons were subsequently enclosed to give

the parochial boundaries as shown in the Tithe Maps. The virtual snapshot of

the northern edge of Blything in 1086 illuminates the process of clearing and

settlement of upland forest. The

process had long been a feature of the spread of the English, as families moved

west, exploring Suffolk’s network of streams to access the heavy clay

cornlands.

The parish touched most people's lives through its role

as a form of local government and as a significant landscape feature, which

defined a circuit of territory to which local people may have felt an

allegiance. Evidence for the social meaning of boundaries is found in acts of

boundary marking and related perambulation ceremonies and through written

records, sometimes involving maps. In the primary definition a premium was

placed on local knowledge, especially of the older parishioners. Acts of

boundary recording could enhance a sense of parish consciousness and community.

The peculiar arrangement of

Halesworth’s northern parish boundary as it was mapped in the early 19th

century, in relation to Wissett and Holton, with the detached portion of

Halesworth embedded in Spexhall, requires some explanation. The fact that Spexhall church appears to

have originated to serve a chapelry of Wissett, suggests that Spexhall was

actually a post-Conquest community created on the eastern plateau lands of

Wissett. Wissett’s pannage for 300 pigs

reinforces the idea that there was a large tract of woodland available to the

parish that was probably the plateau land upon which Spexhall was eventually

established as an independent parish, where it shared common rights with

Halesworth and Westhall.

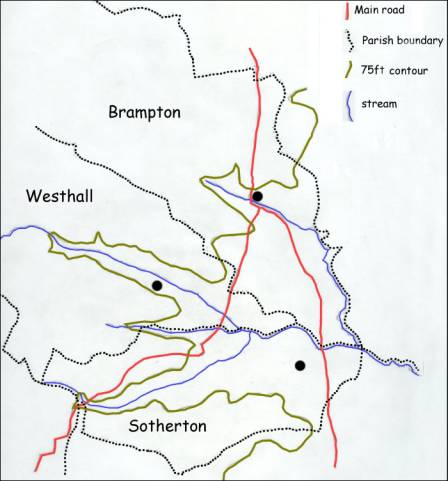

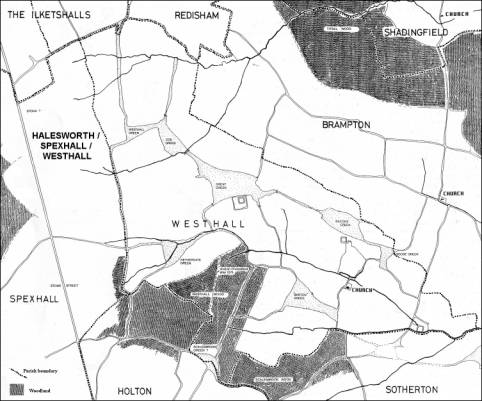

Fig.

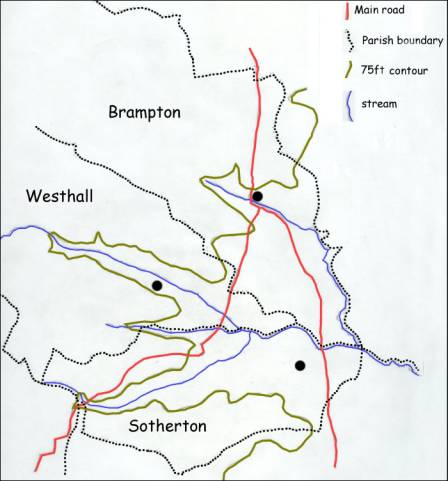

2.11 Plateau-edge parishes of Brampton, Westhall and Sotherton

There are also intriguing

arial relationships between the lands situated at the edges of several parishes

immediately to the north of Halesworth.

Uncertainties of ownership in these flat lands with no obvious physical

markers, seem to have existed where Halesworth impinged on the territory of the

three north-eastern parishes of Brampton, Westhall and Sotherton, to the east

of Stone St. These three parishes are

situated on the edge of the clay plateau with their communities focused in

three small valleys with unnamed streams feeding the River Blyth beyond

Wangford at Wolsey’s Bridge (Fig 2.11).

If their churches are taken as the main points of settlement, it is

clear that the 75 ft contour is a key to the original suitability of these

valleys for their first communities.

From the churches, the parish lands rise up the valleys to the west,

where, in the case of Westhall, the boundary is for the most part aligned north

to south, parallel to Stone Street, from which it was separated by about half a

mile of territory belonging to Halesworth and Spexhall. The northern boundaries of Westhall and

Brampton coincide with Blything’s Hundred boundary, as did Halesworth’s

detached northern block of land.

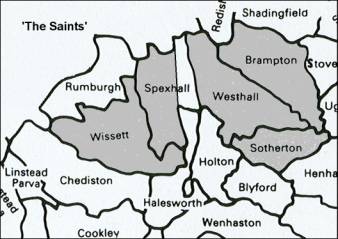

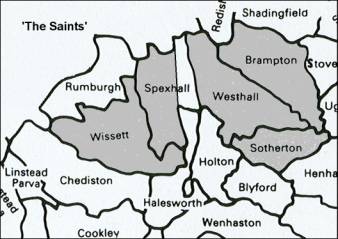

Sotherton is the smallest of the three villages and

abuts onto Holton and Blyford. The contiguity and shapes of their 19th

century boundaries (Fig. 2.12) is strongly suggestive that they were originally

one community, with a western nook, or valley, which became a separate

village. Sotherton or ‘south

community’, which is mentioned in Domesday, is a candidate for an early

division of Brampton. Westhall has to

be ‘west’ of something, and indeed, it forms the western boundary of Brampton. The name ‘Brampton’ is common throughout

England and has been equated with ‘burnt place’ i.e. a community laid waste by

fire. This is a clue to a point in time

when a disaster overcame Brampton in Suffolk, after which three new nuclear

villages, Brampton, Sotherton and Westhall were created out of the one

territory. Regarding their origins, in 1086 Brampton had about three

times the farming activity of Sotherton, which from its holding of 100 hogs was

probably largely a woodland area. The

actual dimensions of Sotherton were given as 1 league long by half a league wide. Brampton’s size was not recorded.

Fig

2.12 The ‘nuclear’ communities of Wissett and Brampton

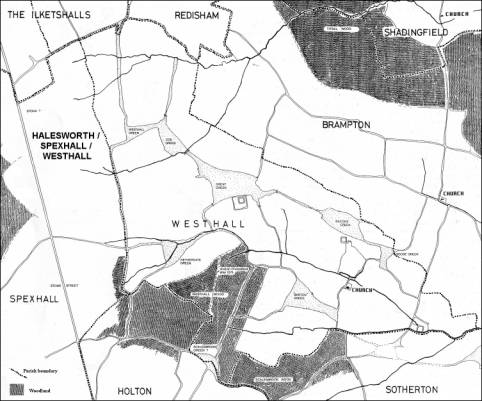

Warner, in his booklet, ‘Seven Wonders from

Westhall’ has mapped the probable 14th century distribution of

woodland in the three parishes (Fig 2.13).

His map shows a southern block straddling the boundary between Westhall

and Sotherton. This pattern of

distribution, taken together with the relatively large area of common land in

Westhall that was probably derived from woodland, indicates that Westhall was a

post-Conquest creation by the division of Sotherton and its settlement from

Brampton. Its relatively large area of

common land was probably a legacy from its origins as a block of wood pasture. From an examination of the plan and

Romanesque features of Westhall church, Warner favours a late 11th

century origin for its foundation as a stone-built chapel, which was

subsequently embellished with an apse with a well-carved ‘Norman’ chancel arch

and portal in the next century.

What have these ancient topographic features of the communities

north of the town to do with the development of Halesworth? First there is an etymological unity with

the name 'hal or hall' used to describe an out of the way place. The name Halesworth (various early spellings

are Halesuuorda, Haleurda, Healesuurda) may have originated as a local

description of 'the farming community (urda) of the nook (hale)'. Hal or hall

is common to the cluster of Spexhall, Westhall, Titshall (an isolated wood in

Brampton), Spexhall and Ilketshall. In

line with this, there is evidence that these communities spread out from small

well-watered valleys at the northern edge of Blything Hundred, up onto the

intractable wooded clayland of the high plateau. This plateau between the Blyth and Waveney catchments was

probably an impediment to north-south communication from the earliest

times. In this respect, Stone Street is

regarded as a local engineering initiative of the Romans to drive a route

across the impenetrable claylands between Halesworth and Bungay. This was probably in order to connect the

Romano-British farms of Blything with military installations on the Yare and

Waveney. There is still something of a

mystery about the so-called Roman Roads in and around Blything. Quite often, as in the case of Stone St, the

straight bits connect up bendy bits.

Where there are gaps, the maps often show a dotted line as if the

intermediate section had been destroyed, but without archaeological evidence

for the assumption. A more reasonable

conclusion is that the bendy bits were in existence as a network of local

community tracks before the arrival of the legionary task force, whose job was

to connect up with the next local network on a straight line across a stretch

of impenetrable terrain. After all, these

roads were probably required for the long-distance movement of agricultural

supplies rather than for the rapid deployment of military assets.

Fig

2.13 Disposition of parishes to the east of Stone St in relation to 14th

century woodland

(modified

from Warner, 1996)

Finally, the shape of Halesworth probably developed,

and was restricted, as the result of competition between the ‘nook’ communities

for the empty claylands. In this

connection, Brampton may be regarded as a prototype of Halesworth, with its

church sited above a stream crossed by a minor road. At Domesday it was about twice the size of Halesworth and like

Halesworth its lord successfully petitioned Henry III for a market and fair

(1251), as did the lord of Sotherton (1226).

The latter rights were later transferred to the secondary community of

Westhall. This signalled the beginning

of the decline of Sotherton relative to Westhall, and by the 17th

century it was only half the size of its northern neighbour. At this time

(1674) Brampton had 20 households, Westhall had 46, and Sotherton had 21. In

contrast, Halesworth had 226 households at this time, and the retail

revolution, which boosted the population of Halesworth, had bypassed its

northern neighbours, and even the coming of the railway did not significantly

enhance their agrarian economies. In

contrast to Halesworth, they remain to this day as sparsely populated, out of

the way places, and rare examples of extreme rurality.