Measuring the height and age of a tree

How to measure the height of a tree

The height of a tree less than about six metres tall can be measured accurately with a rod. A tall tree can be measured easily and reasonably closely by several home-made methods, and more accurately and reliably by an instrument. Exact measurement of its height is, however, normally impracticable. Even climbing the tree can rarely solve the problem. The path for the tape down the bole cannot be quite direct, the precise tip often cannot be seen by the climber or judged closely to be level with his rod, and the tree may lean.

Height is reckoned from the highest point of the crown and this may, in an old, many headed conifer, and in a broad, domed broadleaf tree, be many metres from the central axis. Its position has to be decided from a distance and the point directly beneath it estimated from under the crown. The bottom of a tree is the highest point to which thesis reaches up the bole. This prevents the extended bole and roots on the downhill side of a steep slope from counting in the height.

Having observed the points between which the measurement is to be made, the next thing to decide is the point from which to make it. Accuracy is best at a distance from the tree which is equal to its height and from the same level as its base. In fact even quite a marked slope makes little difference because measurement is made down to the base as well as up to the top, but an uphill shot from much below the tree is best avoided. So a rough estimate of the height of the tree - 20, 30 or 40 m - is made and a position found at about the equivalent distance (with an instrument an exact distance is required) as nearly level with the base as possible, from which the top and the bottom can be seen. A tree with an obvious lean is sighted at a right-angle to the direction of lean if possible. If it cannot be, then, as is worth doing for all very tall trees, two shots from opposite directions give a mean which is the height.

Interestingly, unpractised estimates by eye usually much underestimate trees of six to twelve metres, and grossly overestimate trees of 25-30 m in height.

Method I

The top of a tree, its base and your eye form a triangle with a right-angle between the stem of the tree and the ground. Hence, when the whole tree makes an angle of 45¡ from your eye, the two sides formed by the tree and your distance from it are equal. You are the same distance from the base as the tip is, and were the tree to fall, its tip would land at your feet. This distance can be measured precisely along the ground. To find the point at which the angle is 45, a miniature of the real triangle is made. Break a stick so that its length is exactly equal to the length of your fully stretched arm. Hold it vertically at arm's length. Move to where the top and bottom of the stick align with those of the tree. You are then at the desired point (Fig 1)

Method 2

Unlike Method 1, this requires two people. A small nick is cut into a ruler, or a rod similarly marked, at the one-inch mark or at five cm on a 50cm rod. Hold the ruler at full stretch (which is a constant and the easiest distance) and move to where the tree top and base line up with those of the ruler. Now ask your assistant to move a white marker (a notebook page folded into a broad triangle will do) to bring it exactly into the notch. The height at which this occurs is one twelfth or one tenth, depending on the measure used, of the full height of the tree (Fig 1).

Method 3

The sun is not always out and tree shadows are not very often thrown on to open ground, but for lawn specimens the shadow method can be useful. The height of the sun at any hour and day can be determined by reference to a Nautical Almanack but this process can be short-circuited by a simple device. The length of the tree-shadow is compared with that of the shadow of a two m rod taken at the same time and the height arrived at by simple proportion (Fig 2).

Method 4

Using a Hypsometer

The volume of a standing tree can only be accurately measured by taking the height to timber point with an instrument, and by climbing the tree to take the quarter-girth at half this height. This, of course, can only be done for special reasons.

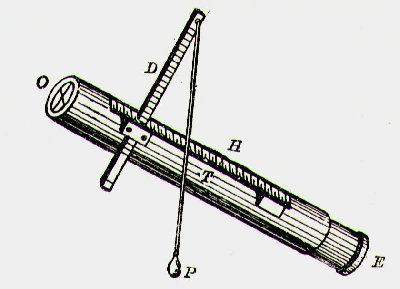

A hypsometer is an instrument for measuring height. A free-hanging needle reads directly on several scales or else a bob rotates a cylinder with scales against a marker. Most have scales for distances from the tree, marked 15, 20, 30 and 40 and these can be feet, yards or metres, whichever is used for the baseline. Hypsometers are expensive. Workable ones can be devised .

Under ordinary circumstances the best procedure is as follows:

The instrument consists of a tube, T, with cross wires at 0, and an eye-piece, E. A toothed scale, H, is fixed to the tube. D is a movable scale with a plumb-line, P, attached to it. To take the height, stand at any point where the top and bottom of the tree can be seen. Then measure the horizontal distance to the tree. Fix the scale D in such a way that it indicates, at the level of the scale H, the same number of units as the}e are in the distance between the observer and the tree. Thus, if the distance is 40 feet, set the scale at 40. Look at the top of the tree through the tube, allowing the plumb-line to swing clear; on getting the cross wires to coincide with the top of the tree, turn the tube gently to the right so that the plumb-line is caught in the teeth. Read off the number at this point on the scale H. This gives the height above the level of the observer's eye. Repeat the operation looking at the bottom of the tree. If the plumb-line is now\caught on the O side of the scale D, add the result to the previous one; if it is caught on the E side of the scale, subtract the second reading from the first. The total given is the height of the tree in feet, if the unit is I foot. Where the tree is very high, or the distance great, the unit may be taken as 2 feet or a yard.

Fig. 14. Weise's Hypsometer.

Thus, if the observer is standing 90 feet away this may be taken as 30 yards, and the scale is set at 30. The height is then obtained in yards, but as the scale is marked to show half units, the result is correct to within I8 inches.

The instrument is simple (Fig 3) and easy to use.

Method 5

When large numbers of trees are to be measured singly it would be tedious to take the height of each tree with an instrument; the work can be hastened without losing much accuracy by using a pole, say 20 feet long, with feet marked on it. This should be propped against the tree, and the woodman can then estimate the length of timber above the top of the pole. Such a pole will be quite sufficient for short trees, but with tall ones the estimate should be checked periodically with the height measurer. After a little practice the length will be obtained with a very fair degree of accuracy. Beginners, when using a pole, usually underestimate the height.

How to estimating the age of a tree

The height and spread of a tree increase with age until senility begins and then they decrease again. Both fail as indicators of age beyond the early years. Diameter and bole circumference must increase every year of life, a ring of new wood being added annually. The circumference, measured at 1.5 m is a guide to the age.

For big-growing trees (not those like apples and holly) the broad rule 'one inch a year' (roughly 2.5 cm) increase in circumference applies regardless of species, region or altitude of site, over a wide span of ages. The reason is that most trees add well over one inch a year in youth and gradually decline first to one inch and then to less. Once they are past one inch a year their mean annual increase becomes nearer to that rate every year and in an old tree it is on or close to it over a very long period. Wood added depends on the amount of foliage, so a tree crowded in a wood or having lost branches adds less each year and may fit 'one inch in two years'. A fully crowned oak 20 feet (about six m) round will usually be about 250 years old.

There are, however, both hares and tortoises among trees. Fast growth, that is three to four inches (7 1() cm), is made each year by the best eucalypts, willows, giant sequoias, coast redwoods, dawn redwoods, some grand firs and poplars.

A few trees grow more than one inch (2.5 cm) a year for less than 100 years and then become very slow. Examples are Scots pine, Norway spruce, sycamore and common lime. Approximate age for these is 100 years plus 2 years for every inch (2.5 cm) of circumference above 10() inches (40 cm).

Fi