Learning to know. Learning to be. Learning to do.

Learning to live together.

These were the four pillars of education for the 21st Century presented by Jacques Delors, at

UNESCO Headquarters, Paris in April 1996 in the report to UNESCO of the International

Commission on Education for the Twenty-first Century,

Learning: the treasure within.

http://www.unesco.org/delors/utopia.htm

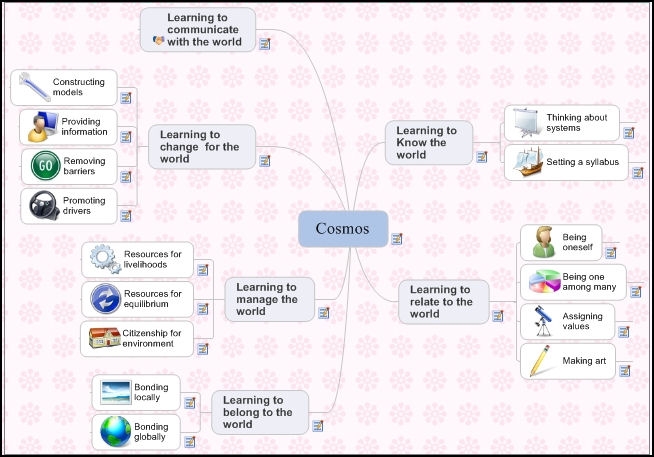

Cosmos is a crosss curicular knowledge system

that develops these four educational strands to make a learning matrix for learning the core

skills and competencies to care for the world.

Two ways of understanding

Running through a days worth

Of sights and scents,

On the edge of sleep,

There are some intricacies of nature

Requiring no material explanations,

By which we come to understand the world,

And the need for change;

A deep nest of cancer,

Merely trying out its dumbness,

To express a pointless selfhood,

Sparks a scientific endeavour

Far greater than a quest for unicorns,

Which reminds us

That other commonplace complexities,

Just as puzzling at the time,

Simply require acceptance of beauty,

An explanation for preservation complete in itself,

With no dream of a cure,

Like the spinning sense of balance

In a skyball of streaming starlings,

Each a magnet for its neighbour,

And a street full of transfixed spectators,

Or mouthed kisses brushed,

Like pale gems on the wind.

Cancers, starlings and him and her,

Are imaginative obsessions

Of a bewildered ape,

Programmed to double take,

And invent God for completeness,

In the space it shares

With other things,

All too thin and long term

To survive a fast learner.

FIRST LEVEL MATRIX

Explanations for a material universe must be based on material causes. Mathematical analysis

of the beginnings point to our universe as one of many that have been set in motion and we

humans have become part of it by accident. Through the ages, religion has conditioned us

to believe that Earth is a gift over which we have been granted dominion by a supernatural

creator. The declines in religiosity and the old supernatural theocratic outlook on creation

have shifted attitudes towards our planet from dominion to stewardship. This has provoked

thought about the relation we bear to the universe as living parts of a vast cosmos that has

existed time out of mind, where we can be only onlookers. On our tiny planet at the edge

of a minor galaxy we are able to contemplate a hundred years of detrimental impacts of our

uses of planetary resources. We have evolved as an integral part of Earth and this has

given us the power of predicting the consequences of our actions and learning with the long

term future of the world in mind.

On Earth's surface, in everything we do from painting a house to producing children we are

integral with all its ecosystems. This view of humankind as being part of complex and

relatively fragile chemical systems, together with our evolved ability to make plans for the

future, provides the opportunity to cooperate in maintaining the ecological processes that

sustain our planetary home. We have the technical ability to change our behaviour, but that

is not enough. We need a world knowledge system that is basic to all subjects and which is

based on a reordering and amplification of the UNESCO learning principles as:

Learning to know the world (by crossing subject boundaries)

Learning to relate to the world (through material science

Learning to belong to the world ( through mind, body and spirituality)

Learning to manage the world (by bonding locally and globally)

Learning to change the world (by behaving sustainably)

Learning to communicate with the world (by understanding traditions and needs of

others)

Science has shown us that materially we are as just one of many beings sharing a common

origin. This biocentric view of humankind raises the value of Earth's mothership into the

realm of the spirit. We have a spiritual vision of our relationship to Earth because as science

finds new explanations for our material being it also increases the mystery of the unknown.

Mysteries, yet to be explained in material terms, are expressed in the great spiritual

emotions of sublimity, grandeur, and majesty. Like scientific endeavour, these emotions

have also evolved for us to know the unknown. They represent ways of knowing which,

although they have preceded the social evolution of religion, nevertheless define what is

sacred and hallowed. That is to say they are part of mental processes, of which we are

unaware, that endow objects and events with beauty, reverence, awe or respect. By

means of these notions we can communicate the innermost and most central parts of a

thing powerfully and non- scientifically. At a mudane level they prompt us to choose where

we go for holidays. At higher levels they allow us define things 'of the heart', meaning they

are cherished and out of the ordinary, like when we say 'time has stood still'. Knowing

things of the heart is the basis of motivations to care and protect. Similarly, 'soul' is a

spiritual expression for the innermost part or moral nature of a thing. A close spiritual regard

for a sacred mother earth endows the planet with qualities of mysticism or exaltation. This is

basis of desires of righteousness to take the earth into the soul and care for it, irrespective of

what it can provide for the material life of groups and individuals.

Of all the living things taking planetary sustenance, we have, through trade and its lack of

care for its sources of raw materials, become the greatest factor disturbing earth's

ecological and climatic equilibria. Because we are able to think spiritually about Earth as

Mother from which we receive nourishment, we cannot receive all these privileges without

bearing obligations to keep, to cherish, and to cooperate. In taking there must be giving

and giving allows taking. Scientifically, the degradation of the planet is plain to see. It is

obvious that human self interest has caused the current environmental crisis. This leaves an

appeal to moral precepts based on a spiritually based environmental ethic, and an

heightened awareness of inequalities of taking and giving between peoples, to move us from

the economic realm of trade to the realm of morals, and thereby increase our spiritual

stature.

The workings and produce of a sacred earth are also sacred, so we are allowed to endow

them with a moral significance. In this respect, as beings steeped in spirituality we are

individually obliged to apply this behaviour, and make righteous use of all our knowledge

to help equilibrate a better social order with Earth, based on obligation and service to its

ecosystems. This is also the basis for conceiving and applying national and racial morals to

unify humankind. It then becomes a social responsibility of education to teach a sacred

understanding of the moral obligations we bear to our Earth as living parts of the vast

creation. For this to happen, an understanding of things of the spirit must be placed at the

centre of national curricula.

Non-religious people regard spirit as an educational metaphor. It is a means to express

subtle ideas, attitudes, and feelings. For the religious, it's a force, closely aligned to the

concept of heaven, and the world of angelic beings. For most people it is exemplified by

an addiction to sunsets. The internationalist teacher Krishnamurti discussing sunsets,

lamented the fact that we often miss the best part of them. We are so busy documenting and

trying to capture the sunset with a camera, we miss the best part of it as a transient

experience, where each moment offers subtle changes in colour, in the positioning of the

sun, in the silhouette of the trees and the cast shadows. He says, be still, and experience the

full spirituality of each moment the desire for time to stand still.

The difference between a material explanation and a spiritual explanation is on the one

hand to compare the satisfaction obtained by measuring angles, the position of the sun to

the horizon, making a table and plotting a graph etc, and on the other simply watching the

ever- changing colours and rapid darkening of a sky with its shifting patterns of clouds.

In personal relationships, the fact that loving seems to depend on the intraction of a small

hormone called oxytocin with brain cells, does not add to our understanding of what it is like

to be in love. The latter route to understanding sunsets and love involves registering beauty,

art, innocence, wonder, inspiration, like on another occasion you might stop to enjoy the

intricate weaving of a spider's web - a very personal understanding and something you may

or may not wish to share with others. The spiritual value of a spider in a species survival

plan is much more than the size of its population and much easier to describe.

Here is how Roger Deakin, writer, broadcaster, conservationist uses all senses to evaluate

the colours and culture of the species and ecosystems of Suffolk county's ancient commons

or greens, which he calls 'our aboriginal lands'.

"I've lived beside Mellis Common for thirty-something years and now feel quite

as attuned to its rhythms and moods as people do who live by the sea. I stand

at its tree banked shore each morning to gaze across acres of rippling grass to

streaky horizons and get the measure of the day's weather. Its sunsets, too, are

a source of inspiration and a topic of our local conversation. Somehow, the

deep under- blush of sorrel in the waves of green and purple grasses, pools of

buttercups and ox- eye daisies, reflects the crimson evening skies.

But the best way to view a common is to submerge yourself in it: to dive

beneath the surface of cocksfoot, Yorkshire fog, Timothy, and foxtail, and

discover the teeming life in the world of lesser herbs and beings beneath. You

delve about with a grass-stern in the cuckoo spit on a thistle and discover the

green frog- hopper nymph inside, a tiny moon- creature staring back at you

with pencil-point eyes. You watch a bee- fly hover before the tiny white

flower of Jack-by-the- hedge.

Thus, commons are part of the much older, more intimate, landscape of

walking, well known to every villager until quite recently. Now oases of ancient

grassland, they have always been part of a fluid, interconnected system that has

evolved organically through many centuries of people, livestock and wild

animals moving about between them Wortham Ling, Wortham Common,

Burgate Great and Little Greens, Stubbings Green and Mellis Common are all

joined by paths and tracks like the Furzeway, Stonebridge Lane, and Buggs

Road. The lovely raggle- taggle commons of the Saints around South Elmham

are also conjoined by paths and old roads that wind about so much that the

area is Suffolk's Bermuda Triangle".

"The Tragedy of the Commons" is an influential article written by Garrett Hardin in 1968. The

article describes a dilemma in which multiple individuals acting independently in their own

self-interest, can ultimately destroy a shared limited resource, even where it is clear that it is

not in anyone's long term interest for this to happen.

Central to Hardin's article is a metaphor of herders sharing a common parcel of land (the

commons, similar to Deakin's Suffolk Greens, on which they are all entitled to let their cows

graze. In Hardin's view, it is in each herder's interest to put as many cows as possible onto the

land, even if the common is damaged as a result. The herder receives all the benefits from the

additional cows, while the damage to the commons is shared by the entire group. If all herders

make this individually rational decision however, the commons is destroyed and all herders

suffer.

Hardin asks for a strict management of global common goods via increased government

involvement or/and international regulation bodies. In this he is calling for a response to

ecosystems such as oceans and forests that have spiritual as well as material values.